“L. Ron Hubbard does not have the neurological excuse for the declining quality of his work. I think it can only be attributed to the fact that he was a colossal asshole.”

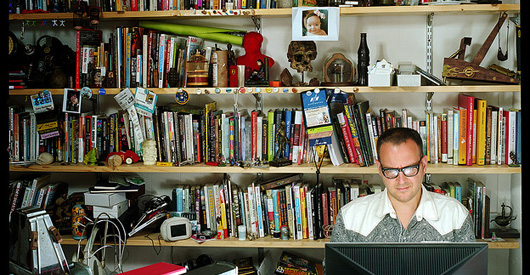

Cory Doctorow attended four universities but never completed a degree.

Today, the Toronto native is a wildly successful sci-fi writer, journalist, and public speaker.

What’s the motto of the story? I’m not sure.

What is certain, however, is that much of Doctorow’s success is unconventional.

Doctorow is a leader of the “copyleft” activist movement and a huge supporter/user of Creative Commons licenses. He simultaneously sells physical copies of his books while posting them for free online, and touts this as a successful business model that other authors should follow. It’s an unusual recipe that has worked wonders for his bank account.

In a 2006 article in Forbes Magazine, penned by Doctorow, he says, “I’ve been giving away my books ever since my first novel came out, and boy has it ever made me a bunch of money.”

Sounds cocky, perhaps, but when you believe in an idea, go against the grain, and achieve success it’s fitting to brag a bit.

His militant belief that copyright needs to be more liberal, and that people are better off sharing, is best understood by this statement from Doctorow: “It’s very hard to monetize fame, but it’s impossible to monetize obscurity.”

With that ethical mindset, Doctorow’s success has spread across multiple platforms. He writes regular columns for The Guardian, co-established the popular website Boing Boing, and publishes his thoughts raw and unedited on his blog Craphound. He is also a prolific author, having started writing at 17 and publishing his novel, Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom, at 32. His new novel Rapture of the Nerds, co-written with popular British author Charles Stross, was released Sept. 4.

Throughout his prolific and diverse career, Doctorow has established himself as a distinct and influential voice on all things related to technology, the Internet, and copyright. His opinions are often radical enough that’s he’s labelled an online activist.

His writing style, equally so, is characterized by his own brand of wit and humour. His opinions are sharply expressed and resonate with thousands around the world.

With an eclectic catalogue and many counter-cultural views, there is much I WANNA KNOW about Cory Doctorow.

I caught up with Doctorow in Toronto on September 19th, 2012, when he was in town for the Glenn Gould Variations.

From sci-fi writing, to the limits of science, to L. Ron Hubbard, to fan fiction, we cover it all.

. . .

RK: Your latest book “Rapture of the Nerds” is receiving glowing reviews. There is often some mention, however, of how inaccessible the language and references can be. Do you worry about your work alienating a certain audience? Or, is crafting a challenge read part of the thrill?

CD: Science fiction has always been written as kind of a riddle for the reader to figure out. The whole point is to stop the reader and force their imagination to conjure up something that would otherwise take thousands of words to describe. But even more so today we live in the age of Google. So writers should feel free to add in references that provide richness and depth to readers who take the time to look them up.

For example there’s a sequence in Rapture of the Nerds where Charlie wrote a reference to Hilbert’s hotel. We’re talking about an infinite simulated hotel that has been created by turning all of the moons of Jupiter into giant computers that are used to simulate it. I know Charlie wrote that because I’ve never heard of Hilbert’s hotel. But if you look it up as I did later, it’s rather funny. If you don’t look it up, it’s just a thing that your eye passes over. It’s just there for the reader who wants to find it.

RK: You co-wrote this book with Charles Stross by sending chapters back and forth and continuing each other’s plot lines. This is the third book you’ve done together like this. What was that process like this time?

CD: I’d say that the first one was very easy in cycle. The second one was more difficult and a bit argumentative. This is where we kind of stalemated on each other’s edits. Like, “I don’t really see where you are going here.” That happened a lot more partly because we inherited the first story so we then had to write a piece that followed on naturally from that first story. And the third one I think was smooth again in part because we did more outlining for it and in part because we’d come a long way since then. We’d both written a lot more, we’d both collaborated a lot more.

RK: You once said that “science fiction writers don’t predict the future (except accidentally), but if they’re very good, they may manage to predict the present.” A lot of your writing presents a world where technology will blend with everything (singularity). Is this a reality you can actually imagine occurring soon?

CD: Well, I think it’s more like we’re trying to expose the kind of historical and spiritual underpinnings of singularity thinking. Singularity looks like a response to technology and its acceleration. But, it can also be understood as a continuation of eschatological thought that has been going on for a very long time.

RK: Do you think there are limitations to technological invention?

CD: There are some limitations we understand very well. We’ll never get to the end of Pi. There’s a whole class of problems that are called NP-hard and NP-complete that involve things like the shortest route for a travelling salesmen to take among a bunch of cities, or the most sufficient way to pack a bag full of irregular objects. Both of those are considered insolvable problems above a certain level of complexity.

There are even things like chess games where even if you wrote a piece of software that played every possible game of chess to find all the winning ones so anytime someone makes a move the computer knows all the possible moves that will result in a win. We’re pretty sure that’s not possible because there are more possible chess games than there are hydrogen atoms in the universe. Storing all those chess games would require figuring out a way to store chess games in something that is smaller than a hydrogen atom.

There are a whole bunch of things that human beings do well, like coming up with approximately best solutions to packing objects in a trunk. We don’t have any way of getting machines to do particularly better.

RK: Are there technological advancements that you think can go too far? For example, cloning.

CD: Gosh, it’s hard for me to imagine that someone would say we shouldn’t try and understand the genome, unless of course that person was an actual technophobe; someone who has an irrational, pathological, fear of technology. Understanding the genome is not a bad thing in and of itself. My feeling is that when we try to predict the ethical dimension of those sorts of discoveries we tend to overestimate the extent to which it could magnify the problems we have today and underestimate the extent to which it will create new problems.

We worry about things like sex selection in societies that have very large advantages for families with male children, like China and India. The more we understand about genetics the worse that gets. And, it’s probably true but those problems don’t need major technological advancements to be problems, they’re already problems.

The really gnarly problems with genetics are whether or not we are interested in hybridizing the human genome, or discovering behavioral queues in our genomes so we can shape society to a eugenic program. The mistakes we make are probably more interesting that the things we get right.

RK: So, what you’re saying is that if we can clone Rob Ford, we should?

CD: Cloning Rob Ford wouldn’t tell us anything one way or another, unless you brought him up in the same way, you wouldn’t get Rob Ford. I’m way more worried about Rob Ford being in charge of anything to do with education or town planning. That’s way more likely to give us more Rob Ford’s than merely cloning his genome. The really scary way that Rob Ford perpetuates his ideas is the same way Mike Harris did when he gerrymandered the districts in Toronto so that people like Rob Ford could be elected by the suburbs even as the downtown core voted overwhelmingly against him.

RK: You have a very defined literary voice. How did your writing style evolve?

CD: I don’t believe in talent, I believe in practice. Talent gets you so far and no further. In the writing workshops and programs I went through there were lots of very talented writers who ultimately didn’t go anywhere with their writing careers because they decided it wasn’t worth the effort. They got far enough along to see it was going to take a lot of work to get themselves up to speed to the point where they were working professionally. But, seeing that it wouldn’t pay very well and take a lot work they concluded, and I think correctly, that if can stop writing you probably should. It’s not really a very good career choice. It’s a satisfying artistic location, but as a career becoming a writer is about as reliable as saying I’m going to be a professional lottery ticket buyer. If you someday plan on supporting a family don’t become a writer. While there are some writer’s who support families, most who set out to become a writer never make enough to support their families. Have a Plan B.

RK: Where would you rank L. Ron Hubbard in the echelons of sci-fi writers?

CD: He wasn’t a very good writer. He wrote one moderately good book called Fear. The rest of his novels are very bad and they got worse the older he got. Robert Heinlein’s novels got worse the older he got, but then they found a benign tumor that was reducing the oxygen to his brain. After they operated on him his books got better. As far as I know, Hubbard does not have the neurological excuse for the declining quality of his work. I think it can only be attributed to the fact that he was a colossal asshole.

RK: You have always been a supporter of fan fiction. Creative commons helped establish the ability for writers to legally do this. Do you see the explosion of Fifty Shades of Grey as a step in the right direction for the movement?

CD: Sure. Every novelist borrows from Cervantes who invented the Western novel. We say, “It’s not unoriginal to write a novel,” even though Cervantes invented it. The thing he did was kind of like plumbing. The thing you’re doing is like art. Inventing the form is just engineering and here we are adding art to it. I think what he did was magnificently creative, and I think what people do when they write a novel is magnificently creative. That creativity is best understood by understanding the aesthetic experience of the reader. If the work makes the reader pleased, or moved, then something artistic has been added to it. We are inclined to say that all the stuff people currently get paid for is the artist part, and all of the stuff we don’t pay for is the plumbing part, and so we say writing the novel is art and fan fiction is not. Generally speaking the commercial and cultural definition of art is to follow the money and now that this lady has presumably made a whole lot of money we’ll once again be able to consider it as art again. We know that fan fiction is art, of course it is. West Side Story is art. My Fair Lady is art. These are all fan fiction.

FOR MORE INFORMATION ON CORY DOCTOROW:

1) Check out his website at www.craphound.com

2) Check out his publisher’s site and profile at http://www.tor.com/bios/authors/cory-doctorow

0 Comments