“I get a lot of hate mail, death threats and rape threats..I think the violence of their response to me reflects just how frightened they are by these ideas. They accuse me of blasphemy and various other things, but actually it reflects their deep seated insecurities…What if my ideas about the world and the next life are not real?”

An atheist, a Biblical scholar, and a Brit walk into a bar.

That’s not the start of a joke; it’s just Professor Francesca Stavrakopoulou unwinding after a long day of studying the Bible and warding off death threats from her critics.

Stavrakopoulou is Professor of Hebrew Bible and Ancient Religion at Exeter University in the United Kingdom. She’s dedicated much of her life to intensely studying one of the world’s most popular and controversial books. Many scholars have chosen the Bible as their academic muse, but a few things make her stand out, and attract extra ire.

For starters, her last name really seems to confound people. But for Canadians like myself who grew up watching and pronouncing George Stroumboulopoulos, Stavrakopoulou is easy: Stav-Rah-Kah-Poo-Loo. There’s also a co-relation between the name and the work. Growing up Greek, she was introduced to the world of gods and goddesses and had an early fascination with all things mythology. That initial seed led to a passion for studying one of the most impactful religions and religious figures of modern times: Christianity and Jesus.

But perhaps more cofounding, for many, is Stavrakopoulou’s worldview: She’s an atheist. That makes her a rare species in her field. The majority of Biblical scholars hold deep-seated religious views, but Stavrakopoulou doesn’t believe in God; never has and (probably) never will. For some, that’s too much to bear. She must have an agenda. She has no right to study and talk about this holy book. But if we’re really interested in truth and learning about the past, doesn’t someone who can be as objective as possible make sense? I think so. And it’s obvious, listening to her talk about the Bible and Christianity, that she respects believers and brings a level of nuance and grace to heated public conversations about religion.

The respect is not always mutual, however. According to Stavrakopoulou, she’s received numerous death threats and rape threats; mainly from evangelical Christians. I can understand, in some ways, why her research is frightening to fundamentalist Christians. Some of it seems downright blasphemous and to believe it would totally rock your perspective. For example, she argues that Biblical characters like Moses, Noah and Abraham very likely did not exist and are merely mythological characters. The claims are made simply on evidence of their existence…and there’s very little of it outside the Bible itself.

Despite the threats and adversity (being a woman in her field isn’t exactly a walk in the park either), she continues her journey to understand the ancient world and parse out fact from fiction in the Bible. Her latest book, God: An Anatomy, is a thorough unpacking of how early Christians and Jews believed God had a physical body; an idea long lost to history and unknown by many modern day believers.

As someone who grew up reading the Bible and has great interest/respect for its origins, there is much I WANNA KNOW from Professor Stavrakopoulou. I caught up with her via Skype from her home in Exeter.

From her fascination with the Bible, to being an atheist Biblical scholar, to the evidence of Jesus’ existence, to God’s body, to the New Atheists and Jordan Peterson, we cover it all.

***

Before we get into your fascinating Biblical scholarship, let’s start with your last name: Stavrakopoulou. So many seem to struggle with pronouncing it, or get nervous when the time comes. Is it frustrating to have a last name people struggle to pronounce?

It doesn’t bother me as much as when people misgender me. People who don’t know me, and particularly scholars who aren’t in my field at all – even scholars can accidentally just refer to me as “he”. And that just annoys me because obviously being a woman in academia isn’t the easiest thing in the world sometimes. But yes, my surname – I guess I don’t know any different. I grew up mostly in England, where a name like Stavrakopoulou, even though it’s a very diverse multicultural society, Stavrakopoulou still frightens people. I think because it’s so long. I’m so used to people messing it up, and I don’t mind.

You’re an atheist scholar of the Bible. So many people are either confused about why you would dedicate your life and mental health to this line of work, and might also presume your bias must seep into your work. Can you just explain a little bit about how you came to Biblical scholarship and your response to those who think atheists shouldn’t be studying the Bible?

(laughs) There’s a bias for atheists to study the Bible, as if there isn’t a bias for Jewish or Christian people who study the Bible. It’s kind of weird. Because you’re right, this has followed me throughout my whole professional career. Even when I started my academic studies, when I did my first degree and then my master’s and then my doctorate and even doing postdoctoral work, people always said, “But you’re an atheist? Why would you be interested in the Bible?” It’s like, “What? Why wouldn’t I be interested in the Bible?” This collection of texts has shaped so much of our cultural assumptions and preferences and our cultural anxieties. And it just seems to me to be wrongheaded to think that an atheist wouldn’t be interested in the Bible.

I’ve always been really, really interested in religion, ever since I was a kid. I wasn’t brought up religious at all. There were people in my family who were different flavors of Christianity, but not in a going-to-church-all-the-time kinda way. Or the Bible being read every day. Just that kind of cultural Christianity that so many of us grow up with in Western society. But I was always really interested in it. And I think also because of my Greek heritage. When I was really little, I loved all the stories about Greek gods and goddesses. And I just remember not being able to quite understand why there’s all this fuss about Jesus, because it seemed to me like this was completely normal in sort of mythological terms. Here’s a guy whose mum was immortal and whose dad was a God. So what? Why is he so special? How come this guy gets all the attention now and some of those great mythological figures from the past had disappeared? So that’s what got me really into it. And then at school, we had to study some bits of the Bible for our general kind of courses and I found the New Testament really fascinating. And when I found out Jesus was Jewish, oh my God, that blew my mind. As a 12-year-old, I was like, “whoa, that was amazing.”

And then I got to university. Originally, I wanted to study the New Testament, and when I first went to university, I was really interested in the Jewish Jesus, basically. What was the history or the early traditions around this guy and his execution and how come it was such a big deal? And then as a result of that, I obviously discovered the Hebrew Bible; what Jewish people call Tanakh, what Christian people call the Old Testament. I was hooked. I just thought this was the most exciting collection of ancient literature. It’s about history. It’s almost like time travel, you know? It’s like going back in time and trying to understand the ways in which these particular ancient societies understood their world. And understood the otherworldly.

The Bible is the world’s most popular book, and there’s such a variety of ways people would describe what it is. If you’re Christian, you might see it as the divinely inspired word of God. Others will see it as a dangerous and totally ahistorical book. How would you describe what the Bible is?

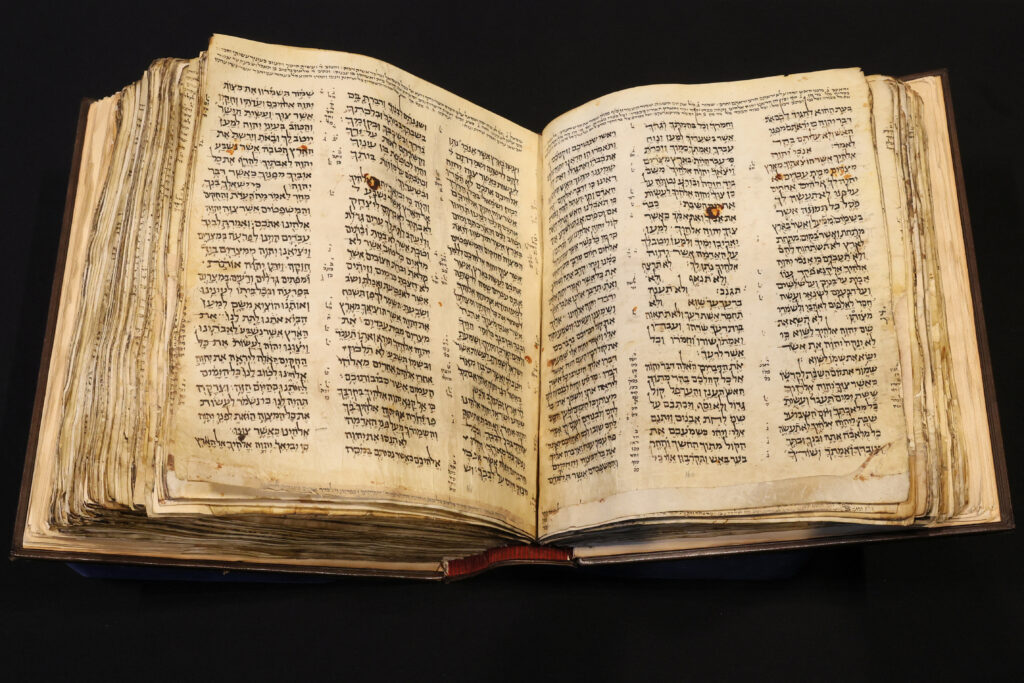

Essentially, the Bible is an ancient anthology of very diverse texts. These texts have not just been crafted and composed, but reworked, re-edited, reshaped, carefully curated, and selected by consecutive groups of Yahweh worshippers initially, and then sort of Jesus followers after that—over hundreds and hundreds of years. And so, in that sense, it’s an ancient anthology, an ancient collection of texts. But the Bible today is also a cultural icon. Whether we like it or not, it matters. It’s like how Shakespeare matters, and the Bible matters in that sense. So it’s a cultural icon, whether you believe it or not. But certainly, it’s not the divine word of God. And if you could travel back in time, you’d be hard-pressed to find an ancient Jewish or early Christian person who would claim that the text was sort of divine. They become sacred. They become other or special or holy because they contain the name of Yahweh or they contain certain divine instructions. But the Bible itself, the idea that it’s somehow immutable or infallible or kind of unchangeable, I think even ancient people would find it hard to get their heads around.

What do you think are the most misunderstood things about the Bible today? What bothers you the most when you hear people talking about the Bible?

You often hear people from politicians to celebrities to your next-door neighbor say things like, “Well, the Bible says.” Firstly, the Bible doesn’t say anything. It doesn’t have a mouth; it doesn’t actually speak. But also, the Bible is massively contradictory. It’s not necessarily ideologically coherent. There are all sorts of contradictions in these texts and sort of juxtapositions. And because these texts weren’t written to be coherent, they weren’t written to be these kinds of authoritative, sacred manuals or rulebooks. They come from very diverse settings and periods of time. And it’s just that the authority that they have become imbued with has increased over time. And interpretations vary massively, both in the ancient context and the contemporary context. So I think that cherry-picking of ideas of what the Bible says is problematic.

What are some of your go-to examples of direct contradictions in the Bible?

Look at the fact that in the New Testament, there are four gospels. They don’t match. They can vary quite a lot in their portrayals of the life of Jesus. The four gospels are very interested in the earthly life of Jesus up to his death and then supposed resurrection after. Someone like Paul, whose writings are the earliest in the New Testament, he’s not at all interested in the earthly life of Jesus. Paul seems to think that the special thing about Jesus, the divine or otherworldly quality, wasn’t inherent in Jesus when he was born. That’s what some of the gospels would tell us. But actually, it was something that happened to him after he died. Somehow his body was completely transformed. It became pneumatic. It became kind of made of spirit rather than flesh. And so for Paul, that’s the point at which Jesus becomes special. That’s why he’s not interested in the earthly life of Jesus. He doesn’t talk about it. Whereas I think that’s what the Gospels, in part, were kind of written to correct. I say correct very loosely. But the gospels are there to fill a gap because people were saying, “How come this person’s body, when he was executed, why did that transform? Why did that become immortal? Why did that become divine or heavenly?”

Even the texts themselves are very comfortable with difference. The Book of Job, a Hebrew Bible text, is all about contradiction. I think it’s about the fact that you can’t sort of navigate or explain or look for what we would call a logical or rational explanation for divine behavior or divine encounters. God can become demonic. That’s exactly how he’s presented in that text.

There are other examples. Certain regulations, certain animals are all perceived as kind of unproblematic ritually or tied to sacrifice. Whereas another text will say, no, no, that animal is completely problematical. Some sexual activities are problematic and in other texts, they’re not. So, you’ve got lots of different examples. But I think the very fact that these texts are so different and diverse should help us step back a minute and not impose a blanket interpretation on anything.

How rare is your worldview in your field? How many other atheist Biblical scholars do you know of?

We’re somewhat rare. There are a few of us, but I don’t come across many atheists, and certainly not many people who started out as atheists when they first got into Biblical studies. I do have some friends and colleagues in the field who used to be practicing Jews or Christians but have lost that faith. That’s perhaps more common. But in terms of how many of us atheists get into biblical studies in the first place, I can think of only two or three others. There may well be more, but yeah.

Do Christian scholars, or even Jewish scholars, of the Bible have blinders on about certain things when they do their research? Does their ideological worldview tend to get in the way of being objective, or are you generally impressed with their scholarship?

Yeah, I’d say particularly with evangelical Christian scholars, there is a real bias. Now, I would not say that the scholarship isn’t good. The scholarship can be great. This is about interpretation. There are so few hard and fast facts in my field, just like in archaeology or the study of ancient history or ancient religions. There are so few certainties that even the way that we interpret archaeological remains is highly contentious sometimes. But even though an evangelical Christian scholar, for example, can be brilliant, a great philologist—a person that studies the nature and relationships between words and their meanings and texts in their languages—you often find that evangelical scholars like philology because they like to think that if they can decipher this ancient text, they can get into some kind of divine truth. But I think that helps people hide because quite often it means that people doing that kind of close, critical textual work don’t have to engage with the bigger questions about historicity, ideology, politics, and social changes. Some scholars who are also big believers and rather fundamentalist in their own personal confessional perspective, I think can often distort or disregard the opinions of other scholars because it doesn’t work in their favor.

Let’s talk about some of the things that they might want to disregard. I saw you on this Australian chat show, and you were talking about Moses, and you basically said, Moses probably didn’t exist. The host seemed a bit stunned, and you could tell it felt like something really controversial. And then in your latest book “God: An Anatomy,” you say historically we can at best consign “Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Moses and even David and Solomon to the realms of fable. And at worst to sheer fantasy”. Are you saying that these figures probably didn’t exist? And if so, how do you know that?

I’m saying that because we just have no evidence. And what I mean is it’s not just that we don’t have inscriptions that have come up on ancient texts dug out of the ground that sort of say Abraham was here or there, there is no evidence for the texts that talk about these characters. The earliest that these traditions could have been written is much, much later, centuries after the period that these texts are describing. And so when you’re looking at the socio-economic and material context in which these sorts of stories could emerge, some people say, “What about oral tradition?” Oral tradition is impossible to track. How do you find proof of oral tradition? So there is no strong evidence to support a lot of those traditions in the Hebrew Bible that talk about origins and ancestors. So a lot of the stuff that we find basically in the Torah, from Adam to Abraham to Noah, to Moses, none of those events, whether it’s floods or whether it’s a mass exodus from Egypt into Canaan, there’s no archaeological evidence for it. With David, we’ve got one reference to the House of David in an 8th-century, some schools say 9th-century texts and inscriptions. If it does refer to the dynasty of David, it doesn’t necessarily mean to say that David himself existed. We know that there was a royal house later on, certainly by that point, that was referred to as the House of David. We have lots of other sorts of evidence that would support that kind of socio-economic setup. But what kind of evidence do you want? So is it a question of probability? Yeah, possibly David existed. I think probably not, but Abraham, Moses, Noah. No. Absolutely not. These are mythological, legendary figures.

Would people in ancient times, living around the same time as Jesus, have believed these figures, like Moses and Noah, were real people?

It’s an interesting question. Did the ancient people believe in them as well? What do we mean by that? I think we have a very different view of both time and history as modern people, and particularly when things are written down in a very authoritative text. It must be true. We know now, I mean look at all the debate going on about AI and all this kind of stuff. We know not to trust what’s written down. Whereas even 30 years ago if something was written in a reputable newspaper, you believed it was true. But we know not to trust written sources. But those kinds of questions, I think, are questions and assumptions that we bring as modern people. Ancient people, I’m not saying they were wholly unlike us; they were very similar to us in all sorts of ways. You know, they could feel the same emotions and passions and pressures that we do. But they also had a very different view of the world. So did they believe that Abraham existed? Probably. But that sense of a common ancestor, we find that in cultures all over the world. Would they have said Abraham was around in the early Bronze Age or the middle Bronze Age? They wouldn’t have had that kind of sense of time. So did they believe in these stories? They were probably just as skeptical about some things as we would be in the sense of manna falling from heaven. Well, how come that doesn’t happen for us? We’re in the middle of a famine.

You’re basically saying that in the Bible, yes, you see these names written down, but outside of that, you just don’t find much evidence, if at all, for some of these figures?

Exactly. It’s not until we get to around the 9th century BCE that we have annals and various texts, inscriptions from the great Mesopotamian empires and Egyptian empires, but mainly the Mesopotamian, the Assyrians, and the Babylonians. They verify some of the names, for example, of various Kings of Israel and Judah. So we know that King Manasseh, he was a seventh-century king. King Hezekiah, we know, these are all referenced in Assyrian texts. But that kind of external corroborating evidence, we just don’t have anything like that prior to the 10th century BCE. But we are on much firmer ground when we talk about the ninth century BCE.

So now we come to the main man: Jesus Christ. He’s the guy that got you into this work, and someone who has inspired me a lot. Did Jesus Christ exist?

A guy we know as Jesus — I don’t think he would have been called Christos, which means Messiah. I don’t think that that label would have been used for him at the time. I doubt that very much — but yes, some guy we now know as Jesus of Nazareth probably existed. He was probably executed by the Romans. That’s as much as we’ve got. We base that on probability simply because given the very short space of time in between when Paul was writing, so say mid-50s CE. Then the gospels as we know them in the New Testament were written late first century, early second century CE. Given that period of time when these texts were written, it seems unlikely that somebody would invent this kind of guy, this inspiring teacher, a rabbi figure, a sectarian leader who would then kick off in the temple and be executed by the Romans. That seems plausible. So probably. But we don’t have any corroborating evidence from the first century CE outside of the text that we now find in the New Testament. Nothing. Some people say, Oh, Josephus makes a reference. A lot of that looks quite problematic. There’s a lot of debate, scholarly debate, around the reference to this Jesus movement and Josephus because it looks like it could be a later insertion into some of those manuscripts.

I’ve heard you refer to the Jesus movement as a ‘minor Jewish cult’, one among many others of the time. Are there other people that we know of that were around roughly the same time as Jesus who were basically making similar claims but just have been long forgotten to history?

Yeah, and not just within a Jewish context, but also within what we might call a Gentile context. In Roman-era Egypt and Roman-era Greece in Roman-era Italy, there are all sorts of other miracle workers and inspiring teachers and healers and people that are said to have resurrected from the dead. There are lots of other kinds of characters around at the time and maybe even this John the Baptist guy, perhaps he was originally imagined to be some kind of divine, or semi-divine man. We find little hints in the gospels themselves and then some of the New Testament texts. There was a tradition in which Herod is worried about John the Baptist resurrecting from the dead because he was so powerful. He was beheaded, but what if he still comes back from the dead? This was a world in which these sorts of things were still amazing and wonderful and incredible and sensational. But there were quite a few people that were going around having all these kinds of wild claims made about them.

It’s clearly a wild phenomenon that the Jesus movement became so global and still remains relevant today. My understanding was always that politics played a big part in this. The Roman Empire adopted Christianity and spreading it helped catapult the religion. From an historical perspective, is this the main reason Christianity spread so widely?

I think partly because it became very politicized, but partly because it was appealing to quite a broad range of people. So particularly the sorts of ideas that we find in the letters of Paul. He’s not writing primarily to Jewish Jesus believers, he’s writing primarily to Gentile communities; some of whom have Jewish origins, but some of whom don’t. And so I think it’s appealing in that sense. It’s got more of a mass appeal. It’s not a very insular exclusive cult, if you like. But I think it spread because of the ways in which these stories were being transmitted and circulated. This is the invention of the codex. What we know as a book. So rather than writing on massive, huge, very expensive-to-produce leather parchment scrolls, they’re now writing on much easier to transport and transmit bits of paper, folded together like a book. So that makes it easier as well.

But also, what seems to have been at the heart of a lot of the early Jesus movement teaching is the sense that the end of the world was about to come. People were like, oh okay, the end of the world, this is huge. The heavenly realm is going to crash into the earthly realm. But if you believe, if you follow this path, your body is going to be completely transformed. We’re going to have these immortal everlasting bodies in heaven. The earth will be no more and we are going to be in heaven forever. And so I think that idea the early generations of Christians really believed that the world was about to end. They were waiting for it. They were ready for it. That’s why Paul, again, spends a lot of time saying don’t bother getting married and having kids because everything’s going to end and we’re going to have these immortal bodies and we’re not going to have to reproduce in order to keep existing down the generations. We are just going to exist forever. That’s a very attractive and frightening idea. If you think the world is going to end, then sign up for this because this is the thing that’s going to save you.

As someone who doesn’t hold a faith about a specific religion or text, you must recognize how scary it can be for some people to have that foundation shaken by new information and historical scholarship. Do you think people avoid scholarly work or digging deeper because it’s kind of scary and disorienting to their worldview?

I think that partly explains why I get a lot of hate mail and a lot of death threats and rape threats and all that kind of stuff. It’s via email and sometimes delivered to my work address. It’s always horrible to encounter, but I think partly the violence of that response reflects fear. I’m so sorry, but it’s normally evangelical Christians that send me this stuff. But I think the violence of their response to me reflects just how frightened they are by these ideas. They accuse me of blasphemy and various other things, but actually, it reflects their deep-seated insecurities about, well, what if it’s not true? What if this is not reality? What if my ideas about the world and the next life are not real? I think people can be frightened. But then there are some evangelicals, for example, some evangelical people, like some scholars in my field, who are perfectly able to do this doublethink where they have their faith and they’re very secure in their faith and they can still do critical scholarly work that does perhaps challenge their ideas. But I think the whole point of faith is that, from what I understand of it as an outsider, faith is faith. The word says it. Even if all the evidence points to something being the opposite, you just believe it nonetheless. And that’s what faith is. It’s a commitment. Those people that find that difficult to do are the ones who I think find me problematic.

What do you think of this idea that the Bible shows the evolution of humanity’s understanding of God? Basically, that the God of the Old Testament is a bit more of a primitive God; one who is vengeful and angry all the time. And then in the New Testament, with the arrival of Jesus, we can understand God as more personal, loving, and willing to sacrifice for us.

I hear this so often. Firstly, it’s very anti-Semitic. It’s caricaturing the God of the Hebrew Bible as somehow a bad, primitive, unsophisticated, violent, angry God. It implies this kind of evolution into the New Testament texts where you’ve got a God who is loving and kind. It’s bullshit. All of the things that you find in the New Testament, essentially all these teachings that Jesus was giving and that his various disciples have given about the nature of God, about how you treat other people, all of the good fluffy stuff is directly recycled from Hebrew Bible texts. Jesus and the first Christians, if you like, were Jewish. They are simply reworking traditional Jewish teaching. And in the Hebrew Bible, God is equally forgiving and loving and kind and gentle and tender and intimate and equally in the New Testament. It’s not just this kind of fluffy, forgiving, loving God. Have you read the book of Revelation? That is fierce, that is about violence and destruction and this is God and Jesus himself wielding the sword and cutting down people. So, firstly, It’s an anti-Semitic trope to say that there’s an evolution in the Bible from the nasty God of the Hebrew Bible to the loving, forgiving God of the New Testament. Secondly, the notion of an evolution I find it really problematic when people assume that ancient societies and civilizations that came before us or are somehow different from our own are somehow unsophisticated or primitive. There are different ways of being in the world. There are people in communities today, traditional indigenous communities, for example, who have a completely different way of being in the world, a completely different way of understanding what a person is. What is the relationship between a person and an animal? Are they the same or are they different? Or do they change? There are different ways of being in the world and to assume that our own Western-inflected perspective is somehow more evolved or more sophisticated, it’s horrific, it does a huge disservice to people of the past or people that just live differently from us. And that’s why that annoys me.

In “God: An Anatomy,” you write that “None of these texts have reached us in their ‘original’ form…All were subject to creative and repeated revision..and editing across a number of generations, reflecting the shifting ideological interests of their curators, who regarded them as sacred texts.” When did that tradition of wrestling with the text and changing ideas stop? When did the intellectualism around the Bible cease?

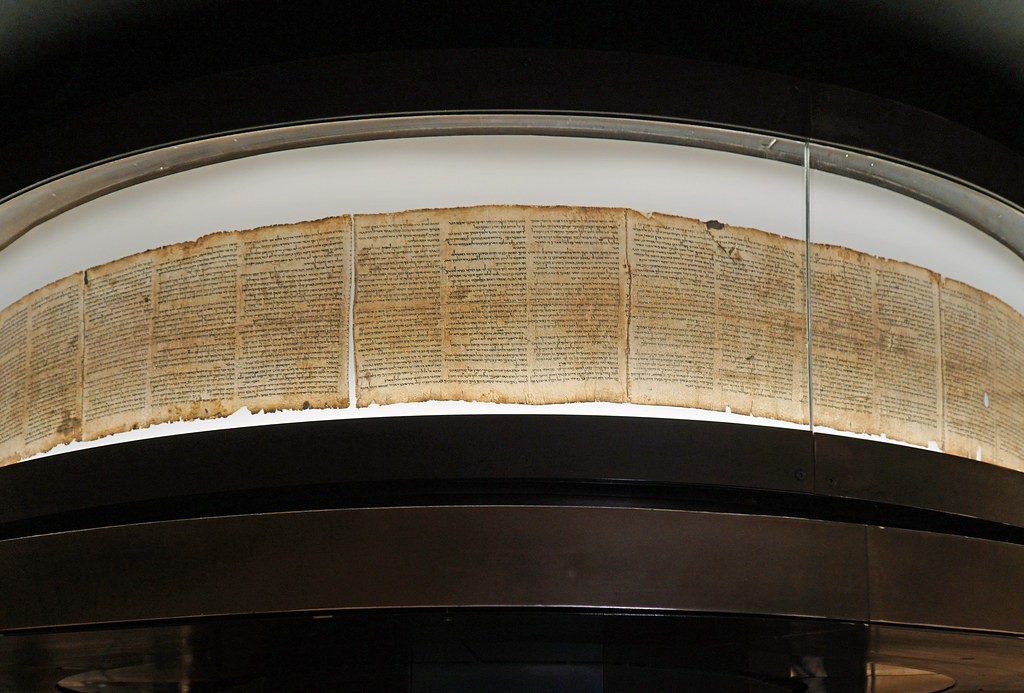

It’s hard to say there was a particular historical moment. There were lots of different episodes along the way that have contributed to that kind of view within certain circles of Christianity in which you just assume that this is an inherent text. But one of the earliest is when early Christians in the first four centuries of Christianity, when they start to canonize texts. In other words, what is the list of authoritative texts? We know there are so many more gospels circulating so many more lives of disciples and saints, and so many more stories about Jesus as a child and all this kind of stuff that didn’t make it into the New Testament. They were deliberately rejected for various reasons. When you kind of get this decision, which are the texts that are in? Which are the texts that are out? That’s the beginning of saying these are legitimate, these are authoritative, and those stories about Jesus and whoever else are not authoritative. That’s when you start to get the language of these are pseudo-apocryphal texts, these are not really proper texts, these are kind of apocryphal stories. So that’s an early stage. But we know that these manuscripts, for example, in the Gospel of John, that very famous, beautiful story about the sinful woman, the adulterous woman who is brought to Jesus and a group of men say, we’re told in the Torah that a woman like this should be stoned to death. And Jesus says, let he without sin cast the first stone. That story about Jesus and the adulterous woman that doesn’t appear in the earliest manuscripts that we have of John. That’s a later insertion, possibly put in around 300 or something. So that was circulating later. But separately, independently of the rest of this material and the gospel of John. So that’s an example that shows you how fluid these textual traditions were. By the 6th century CE that story is now firmly embedded within the manuscript tradition of John’s gospel. But we know that in earlier centuries it wasn’t. It’s the same thing with the Book of Isaiah. Some of those texts from the Dead Sea, the Qumran, you can see on the Isaiah scroll where things that would later appear as main texts in the book of Isaiah appear only in the margins of these scrolls. They’re later editions that gradually work their way into being main text later on. So once you get the idea of a canonized collection of texts, they begin to stabilize. But they were very fluid before that. But I think that’s an important point at which you start to say this text is true and authoritative and that text is not.

I heard a lecture once by Christian thinker Richard Rohr about how the Enlightenment era also created this culture in Christianity of holding up the Bible as an inerrant text and a more scientific manual. Christians doubled down on the infallibility of the Bible to counter secular attacks. Did the Enlightenment change how Christians viewed or studied the Bible?

I think certainly the Enlightenment did. The Enlightenment was drawing on all sorts of different streams of a much older Greek philosophical tradition, but it was drawing very much in ideas of rationality and reason and process and categorizing things. And so I think in that sense, the idea that there is somehow right and wrong truth and falsehood became much more established as a kind of scientific reality, you know? Look at the way that science is treated. Now, I’m very pro-science. I certainly believe in evolution and that I certainly believe that life came to being from some incredible stellar big bang or whatever. So I don’t doubt science. But what I do notice is that sometimes science is kind of assumed to be its own kind of gospel truth. Can you prove it? Well, no, we can’t prove everything. Of course, we can’t. Science is a process of repeating the same experiment over and over and over again to see if you get the same result. But it all depends on the questions that you ask. It all depends on the experiment that you perform. So I think that sometimes science has almost become the untouchable, new icon. If science says it’s true, it must be. But we know that scientific theory is overturned often. But that’s the point of science. The point is to keep testing theories until they fall or break. And then, you know, to find the new theory that explains that. But I do think that from the Enlightenment onwards, I do think we have this sense in which somehow reason, rationality and truth somehow become the polar opposite of falsehoods and fantasy and story and myth. Whereas actually, maybe our reality is somewhere in between.

Your book “God: An Anatomy” unpacks how early Christians saw God, and specifically that they conceived of God having a body. You write, “For the God of the Bible was a deity who not only had a body, but a personal name, a backstory, a family and a host of companions in the heavens”. What compelled you to write a book about this? And why are so few Christians aware of this?

Even as an undergraduate, I was reading these biblical texts and there were clearly references to God’s body and God’s body parts. We’ve got references to his feet and his hands and his face and his breath and his nose and his belly and yet I noticed that when I was at university, a lot of my lecturers and professors, these are very serious people I was at Oxford – a lot of them had this special pleading like this isn’t the same way that the ancient Greeks believed that their gods were corporeal beings. Yes, ancient Greek gods were often human-shaped, but the way that Yahweh is portrayed in the Bible isn’t quite the same. This is poetic, this is allegory, this is metaphor. Well, how come it’s fine to say the ancient Greeks believed that their gods had human-shaped bodies? But it’s not fine to say that ancient Yahweh worshippers believed that their deity had a human-shaped body? It is the same thing. It’s the same stuff. Most ancient cultures in this part of the world at that time understood that deities had human-shaped bodies and more importantly, that humans had God-shaped bodies. And so I thought, why is there still this special pleading? And it’s because later Judaism and Christianity insist on the incorporality and the immateriality of the God of the Bible, whereas the Bible itself doesn’t have that issue. Those later theological preferences have been retrojected back onto the text by scholars and commentators and interpreters and theologians. That became the norm and people didn’t realize that they were viewing these texts with these distorted glasses. So that’s why I wanted to write the book, to say, look how much fun this is? Biblical writers don’t really have a problem with God having a body. What was sensational in the Biblical stories themselves isn’t that he’s got a body, is that he occasionally allows some people to see it or parts of it. And that’s the key thing. You know, an unseen body is not the same as a nonexistent body when it comes to the divine.

So you’re saying that in recent times we’ve seen the references to God’s body parts in the Bible but just assumed they were all metaphors, but there’s clear evidence that the Biblical writers and early Jews and Christians genuinely believed God had a physical body?

Yeah. But why? Why do we assume it’s a metaphor? We don’t assume it’s a metaphor when you’ve got text from a very similar period from a very similar place using exactly the same language. We wouldn’t say they just thought that that was a metaphor because in these ancient cultures, these people actually created statues and figurines of their gods and goddesses who were human-shaped. So when they say I look upon the face of God, what they’re referring to going into a temple or a sanctuary and seeing the cult statue of the deity in front of you. The very fact that we’ve got these explicit prohibitions in the Bible saying you shall not make an image of the divine kind of suggests that that’s exactly what people were doing. You only tell people not to do something if they’re actually doing it. And so that would have been the historical reality of early Yahweh worship. As people become more and more uncomfortable with the idea of actually having a material image of God the notion that he has a body remains. So even the rabbis who are writing up until the 6th century CE, they’re even more explicit and comfortable and colorful about God’s body. They’re talking about God walking around the ruins of the temple and weeping and kissing its broken walls and wearing a prayer shawl on his head. They’re really comfortable.

Do we know exactly who started to banish these ideas of God having a body? Was there a particular historical person or moment that shifted this thinking and led to Christians no longer believing that?

I don’t think we can even talk about everybody. All we have are the texts and the inscriptions that we found. And those text inscriptions usually come from relatively high state elite contexts. So they’re not representative of the views of everybody. So a really good example, when you read the Bible you would think that there was only one temple of Yahweh and that was in Jerusalem. And you would think that by the 5th century B.C., after the Babylonians had destroyed the Jerusalem temple and then it’s rebuilt, that this is the point at which all Yahweh worshippers agreed no more temples here. There’s only one temple in Jerusalem, that’s the only place you can worship. And yet at the same time, we have letters, texts written by a community of Yahweh worshippers who had built a temple to Yahweh on the island of Elephantine in the Nile. They were writing letters to the priests in the Jerusalem temple asking them to support them with money. There’s a Temple of Yahweh, archaeologically it’s there. Yet you would never know that if you just had the Bible, you would think that all Yahweh worshippers had no images, you could only worship Yahweh in Jerusalem. But we know that there was this temple at Elephantine. It’s because the Bible has been privileged as the authoritative source in telling us about the realities of the religious past. But it’s not. The Bible offers a portrayal of the religious past. It doesn’t offer a history of the religious past. And even if it tries to, it’s not a reliable history. It’s because of the privileging of the Bible within our own Western intellectual tradition that leads us to discount or not even look for evidence of diversity in ancient Yahweh worship.

Another fascinating part of your book was the discussion about people believing God had a wife named Asherah. You say there’s evidence that early Yahweh worshippers also worshiped Yahweh in the same temples. In the Bible, of course, she’s referred to as a false God. What can you tell us about Asherah and the shifting conceptions of her in the Bible and among Christians?

The short answer is that we have various inscriptions in Hebrew from the 8th century BCE that refer to Yahweh and his Asherah, and most scholars agree that this indicates a pairing of Yahweh and Asherah. Now, Asherah is the Hebrew name of a goddess who was known all across the ancient Levant, and she was often the consort of the high gods. We have lots of references to Asherah, over 40 times she’s referred to in the Bible, but she’s always referred to very negatively. She’s a deviant goddess and her worshippers are terrible, rebellious, idolatrous Israelites. But we’re also told in those same references that Yahweh says you shall not put the symbol of Asherah next to his altar. We’re told about kings of Jerusalem who put a statue of Asherah in the Temple of Yahweh in Jerusalem. They’re kind of admitting that this is a terrible thing that our ancestors did, but at the same time they’re admitting that Asherah was worshiped in the temple alongside Yahweh in Jerusalem. So most scholars now agree that we should probably consider Asherah to have been Yahweh’s wife and consort. Most deities were paired up with a member of the divine opposite sex. But as monotheism emerges there’s this Pantheon reduction and Yahweh becomes the only God. And so you have to get rid of all the other gods and goddesses in his retinue. And Asherah is one of those victims. But God remains very masculine, very male. He remains a father. He even remains a husband. And a lot of that language that’s used about Yahweh as a husband or as a father gets transferred to his worshippers. There’s this gender queering that most of the writers of Hebrew Bible texts were male writing about men for men, but they cast themselves as the wives of gods, which obviously plays a role in later Christianity when the church becomes the bride of Christ.

Do you think just the lack of female goddesses that have survived in Christianity plays any role in entrenched patriarchy or sexism?

Absolutely. It played a huge role in it. You get echoes of goddess worship in early Christian tradition, like Mary, the mother of God, is elevated up to the queen of heaven. But she is this impossibly perfect kind of woman. She is not sexually corrupted. She’s a virgin. And the flipside is the other Mary that you get who in later Christianity is vilified as a whore and as a prostitute. The absence of the idealized female in the divine or the virginal kind of sanitized version of the idealized female is really problematic and has massively contributed not just to patriarchy but also to misogyny. This fear of women and their bodies and their sexuality and their personhood. I think the world would be a better place if goddesses were still around. But that’s not to say that the cultures that had goddesses weren’t patriarchal. They could still be patriarchal, but goddesses could also play a very important role in the lives of men as well as women.

Switching gears, I wanted to talk about the way the Bible and God are debated in the public sphere. You’re an atheist, but those who often lead the public conversation and debates about this are often called the New Atheists – Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris, formerly Christopher Hitchens. It’s a more militant version looking to convert people out of belief or belittle religion. What do you make of these figures and their stance that the world would be a much better place without religion or the Bible?

I find them really problematic because on the one hand, I don’t think they understand religion. I think religion is a part of the human condition. Religion ultimately is about having a social relationship with a non-existent or otherworldly being or power. And that’s an incredible thing. And that reflects our capacity for sociality and imagination. We can have relationships with our dead ancestors. We have continuing bonds with them. We still go to our grandmother’s graves and lay flowers and talk at the tombstone. That’s still a continuing bond. There’s something fundamental to being human that gives rise to religion and religious behaviors and beliefs. So it’s not going anywhere. People like that misunderstand what religion actually is. Religion is obviously terrible in all sorts of ways for all sorts of different people, but it’s not going anywhere. And so there is no point in trying to dismiss it and ridicule it, not least because not all religious people are bad, unthinking, stupid people. I know a lot of very deeply wonderful, caring, fantastic, clever people who also happen to be religious. Don’t take the piss. Don’t beat down on people just because they’re religious. I can’t bear that. I might not agree with you. I might not share your beliefs, but I absolutely respect your right to have a relationship with another worldly being or power.

I think the second reason is that when not so long ago Donald Trump was holding up a Bible and empowering various conservative evangelical Christians to take away the rights of women to have abortions. You can’t say anything negative about God or Christianity on certain American TV stations. When you’ve got atheists who are being killed in various Middle Eastern and African countries. When you’ve got people whose sexuality becomes criminal because of what people say the Bible says. That in itself means that you need to take religion seriously and you need to talk about it. We need to explore it. We need to challenge it, and we need to engage. So those kinds of New Atheists are problematic because they don’t give religion the space that it needs in order for us to challenge it to help make other people’s lives better.

What do you make of this argument from people like Jordan Peterson that the Bible and Judeo-Christian values are important because they provide social cohesion and set the foundations for Western society, aka the most moral/advanced society the earth has ever known?

I mean, it’s an argument. I would agree only to the extent that, yes, the Bible as a cultural icon has shaped and continues to shape a lot of the cultural preferences and anxieties that so-called Western societies have. So for that very reason, we need to take it seriously whether we like it or not. It is now a cultural icon. It shaped much of our world as we understand it. But as for this notion, this caricaturing of Western cultural values, there’s no such thing as Judeo-Christian. That’s a false hybrid. There’s Jewish or there’s Christian. I think trying to claim some kind of evolutionary model, as I said earlier, is deeply problematic, primarily because it others and marginalizes and renders deviant people that don’t fall into those sorts of categories. And for that reason, I find Jordan Peterson in all sorts of ways deeply troubling and quite stupid.

As a last question, I keep calling you an atheist, and I think you identify as an atheist, but I also know you’re associated with humanist groups as well. I don’t know if you identify as a humanist, but I’m curious about your worldview outside of just labeling yourself an atheist?

I’m a patron of Humanists UK and I share a lot of humanist values. Humanist values are humanist because they are about ultimately the social good. What is doing the right thing, not just because it’s good for me, but because it’s good for other people? That is essentially what makes me excited, this huge capacity we have. We are the most highly social species and we cannot thrive or survive or exist without not just cooperation, but really trying to lift other people up and empower and help other people. That’s the other thing that’s going to get us through anything on a personal level, but also at a community level. And for me, that kind of sense of sociality and personhood extends beyond humans to non-human animals as well. So yeah, for me, it’s a kind of an environmental worldview in which I see us as a part of this planet and we’re all kind of coexisting together. And it seems very clearly evident now with what’s going on with the climate emergency that we need to do what we can to improve the well-being of all life on this planet, because this is the only planet we’ve got and this is the only life we’ve got.

FOR MORE ON PROFESSOR STAVRAKOPOULOU:

- Follow her on Twitter: https://twitter.com/ProfFrancesca

- Purchase a copy of God: An Anatomy

Francesca is so so great. It makes me really angry that she can be subject to so much hate, for not really doing anything wrong. She stakes out a very reasoned, very legitimate, and IMO very balanced position on the Bible and Biblical studies. She is way more empathetic and live-and-let-live than her moronic detractors give her credit for.

And she is completely right about fear as the driver of fundamentalists. So much of their behavior is about making sure that their fellow believers, spouses, children etc., are “protected” and not exposed to “harmful” or “evil” ideas, lest they be seduced and forever tainted by sin. Don’t read Bart Ehrman, don’t get sucked in by wokeism, leftist agendas etc. It’s endless. If their religion and faith is strong enough and made of the right stuff, then they should have no fear. Instead they seem to be the very opposite. So childish.

And she’s also right about Jordan Peterson.