“When you’re wearing a great suit you don’t feel it, it fits you so perfectly because it’s measured again and again to achieve a finality. That’s what good writing is, it’s well tailored.”

For the past 50 plus years, Gay Talese has been meticulously and painstakingly fashioning hundreds and thousands of words together. The result: one of the most accomplished and acclaimed writing portfolio’s in journalism.

Since his early 20s, Talese has been honing his craft writing articles for the New York Times, magazine features for Esquire and the New Yorker, and several best-selling books.

His subject matter has ranged from the underbelly of New York City at night, to the sexual revolution of the 1960s and 1970s, to boxing champions Muhammad Ali, Joe Louis, and Floyd Patterson.

Along the way, Talese and his contemporaries (Tom Wolfe, Truman Capote, and Joan Didion, to name a few) have been responsible for ushering in a new era and genre of journalism: the New Journalism. This is commonly described as non-fiction that reads like a novel. This group of writer’s brought non-fiction back to life by creating exciting scenes, including dialogue, recording minute details and gestures, and using the third-person point of view. For most this required a heightened level of involvement with the subjects.

Like most great New Journalism writer’s, Talese has evolved into a charismatic figure with a defined voice and style. This has been accomplished through great sacrifice and commitment to his work.

First, it is the process of researching that underlies Talese’s style of writing. In this regard, he is a staunch traditionalist: hedoesn’t use a tape-recorder and he refuses to interview over the phone. Instead, he prefers to implement his now infamous technique: the art of hanging around. This involves developing close relationships with his subjects and spending an extraordinary amount of time with them. These countless hours of observing people in multiple environments and situations allows Talese to develop the breadth of character necessary to produce a detailed and realistic piece of writing.

Second, by demanding such an intimate relationship with his subjects Talese surrenders to the task at hand and devotes his life completely. This was most apparent when he wrote his best-selling book, Thy Neighbour’s Wife. He spent close to nine years researching and writing the story of the changing sexual climate in America. The process was intense: he owned and operated seedy massage parlors, lived at a nudist camp, and almost destroyed his marriage. Whether one supports this type of methodology or not, it has produced some phenomenally detailed accounts of history.

Of all his literary achievements one piece has garnered the lion’s share of attention: His 1966 feature article for Esquire entitled Frank Sinatra has a Cold. This piece centered around Sinatra as he approached his 50th birthday. At the time Talese was writing the piece, Sinatra had come down with a cold and it transformed the mood of everyone around him:

“Sinatra with a cold is Picasso without paint, Ferrari without fuel – only worse. For the common cold robs Sinatra of that uninsurable jewel, his voice, cutting into the core of his confidence…A Sinatra with a cold can, in a small way, send vibrations through the entertainment industry and beyond as surely as a president of the United States, suddenly sick, can shake the national economy.” ( excerpt from “Frank Sinatra has a Cold”, 1966)

The Sinatra piece was voted as Esquire’s best feature ever, and is credited as one of the most influential and popular of its genre.

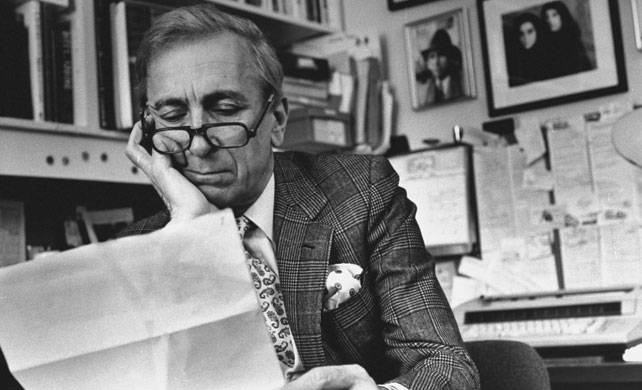

Talese has also developed a reputation as one of the best dressed men in journalism. Born the son of a tailor, Talese adopted from an early age the strategy of dressing for success. Without fail, when Talese is out reporting he dawns his trademark outfit: a suit, hat, and tie; all perfectly tailored of course. The strategy has worked well.

At 80, Talese is still going strong.

There is much I WANNA KNOW about one of journalism’s most experienced and celebrated writers.

I spoke to Gay Talese over the phone from his home in New York.

From the process of writing, to Thy Neighbour’s Wife, to his philosophy on writing and life, to his dream interviews, to what it’s like when he has a cold, we cover it all.

Ryan Kohls: You’ve often described the process of writing as agony. What makes it worth it for you?

Gay Talese: Well, the final result, if there’s any gratification, is when you’re done it and it’s finished and it’s in print and you can read it and say, “I couldn’t have done any better than I did.” So it’s the gratification in work done as well as you can do it. It’s a very personal thing, how well can we do what we do? We only have the energy and time, and guidance that is available within us. So, that’s all it is. It’s just a matter of doing a job, and doing it well. As old as I am, I haven’t changed from when I was very young. Meaning, when I started working as a professional journalist at 22 for the New York Times, I always wanted to do the very best. That continued through my 40s, 50s, until now in my 80s. I bring my same expectation that I have to do the best I can, and I don’t make excuses.

RK: The process of researching your stories also seems to require a great deal of sacrifice, Thy Neighbour’s Wife as an example. Do you think that great journalism requires extreme sacrifice?

GT: Well, it is certainly not a convenient profession. You do have to put yourself out. Thy Neighbour’s Wife took me the better part of nine years to do. The better half of it is the research, and then after the research is a long period of organization. After that, when you know where you’re going and have some sense of direction, then you have to write it. How do you go from point A to point B? How do you direct your readers through what you write? How do you end? All this is plotted much like a ballet is plotted by a choreographer. You have to take certain steps. There’s an opening, a middle, and an end.

RK: When you wrote They Neighbour’s Wife you spent a lot of time in Toronto operating a massage parlor. What do you remember about those days?

GT: I did spend a lot of time there. It was an age of openness at that period. For example, in the early 70s I once went to the Four Seasons Hotel in Toronto and the deck of the hotel was for nudists. We’re not talking about a side street brothel here; we’re talking about a major hotel. And on the roof people who hang out naked. It was amazing. People who go there now can’t imagine that, but I was there so take my word for it.

In 1971, the masseuses were educated women, they were earning extra money in parlors for endevours that had nothing to do with the parlor. They were making good money towards a degree in psychology, or to support being an actor. They wanted to earn money, and it was a way to earn a lot of money on your own hours. Now I think the women are not as well educated, and are more desperate.

RK: As much as you’ve written about iconic figures, you also tend to write untold stories, or the stories of the underdog. Why has that always been so important to you?

GT: The pieces that I think are really challenging for writers are where you’re writing about a person that is not really well known, and you’re writing a magazine piece for the general public. That’s where the challenge is. Where I met that challenge most successfully, I would think, is “Mr. Bad News.” There’s where I write about an obituary writer. Nobody knows the persons name, except for a few people. To be able to write for a general interest magazine, it was Esquire at the time, and not have a famous person, but to just describe this “Mr. Bad News”, Alden Whitman was his name, that was a very interesting way of writing non-fiction. That’s very difficult.

RK: You style of writing is often grouped in as “New Journalism.” Essentially, it’s non-fiction that reads like fiction. What is the biggest challenge of this form of writing?

GT: I feel that it calls upon the writer of non-fiction to bring to the work what a fiction writer brings without making it up. A fiction writer of a short story they imagine a character, or fashion it out of characters they’ve known. It could be a beautiful woman, or a grouchy man. What does it matter? It’s a character. When you’re writing non-fiction you can’t just dream it up, but you have to choose your real, living, character, and write about them so that it brings them into the imagination of the reader in ways that is creative in storytelling but not fabricated. The reason it seems as if it’s a made up story is because the research was so deeply done, so patiently composed that the writer looks as if they made it up because it’s a wonderful story. But it’s not: it’s the result of digging deeply and taking a lot time. That’s the art of non-fiction. It’s better than fiction because it’s real.

RK: You have never used a tape recorder when doing interviews. Why do you avoid the tape recorder? And, why do you think it’s important to not quote people verbatim?

GT: Most people, the younger people I would think, use tape recorders and grew up with them. I was in my mid-career when I heard about the tape recorder, and I didn’t like it then and I don’t like it now. But, if you have a tape recorder and you get people to answer your question and you type what they tell you, they might be telling you something they hadn’t thought of before, and they answer the best they could under the circumstances. What you have is their answer. You have it verbatim, as a record. It’s what they said, and no one can argue about it because you have it on tape. But, just because they said it, and even if it’s very interesting, it might not be what they mean. People say things and don’t always mean what they say, and in retrospect wish they wouldn’t have said it that way or said it better. What I always do after I get to know the people well enough, when we’re talking and they tell me something I think they might be sorry they told me, is I take as a courtesy before I publish to call them up and say, “By the way, when I asked you this and this and this. I was thinking about that and was wondering if you still feel that way.” They might say that it’s right or tell you something more interesting, or enlarge upon what they’ve said.

For example, there’s a piece I wrote called The Loser, it’s about the boxer Floyd Patterson. He used to be the heavyweight champion. One of the questions I asked when I was seeing him was, what’s it like to be knocked out? He gave me an answer, I scribbled it down, and I read it back to him, and he said, “Well, there’s a little more than that.” So we talked some more. I went home that night and I wrote up my notes, and went back to him the next day and showed him what I had and said, “Tell me more.” What I had done is trigger in his own memory what it is like to be knocked out because a question like that you might get a different answer on a different day. When you’re talking to a person with a tape recorder you’re only giving them one opportunity to answer a question, and you’re stuck with it. It’s not finished. It’s not literary. You’re trying to write with a writer’s voice, and yet the quote is just off handed, and that’s why I don’t like to use quotes unless I’ve gone over them with a person, and they’re fully realized.

RK: You have a very polished and tailored style of writing. You also dress in a similar fashion. Is there a connection between the way you like to look, and the way you like to write?

GT: I think that’s fair. The way I write it holds together. It’s like a great suit; there’s a lot of stitches in a great suit. When you’re wearing a great suit you don’t feel it, it fits you so perfectly because it’s measured again and again to achieve a finality. That’s what good writing is. It’s well tailored. It doesn’t fall apart, it hangs with grace and a real dimension of design. There’s something wonderful about something designed like that. Language itself is designed that way. I work on that, and it’s art and craft. I never hand in my first draft, it’s often the fifteenth or twentieth draft when I’m done.

RK: When you write, you write with great detail about characters: good or bad. Is there ever a sense of guilt after you expose things that might not be too flattering about a person?

GT: I don’t think I expose. I do reveal something about the characters, and sometimes about myself as well, but I don’t recall in more than 60 years of publishing anybody that I wrote about that I couldn’t write about, or speak to again, because they were mad about what I wrote. I’m not a person who does “hatchet jobs.” It’s so hard to write well, I labor at it. It’s something I do with great difficulty and I’m not going to expend all the energy and effort on someone I don’t have respect for. Having said that, I’ve written about gangsters and sexual pornographers, but I still had respect for them. I’m writing now about a very good person, a very religious person, who happens to be the manager of the Yankee’s, Joe Girardi. He’s modest, not a braggart, not a superstar athlete, but a good manager. I’ve taken a long time to research this, and I have the same challenge to do this as when I was 40 years younger doing Frank Sinatra.

RK: In order to write a successful piece, you need your subjects to open up completely and share intimate details. Do you find it difficult when people ask the same of you?

GT: No. I feel almost that I have to do it. If you’re calling me from NBC news or your site in Canada, it doesn’t matter. Because I’ve called so many people asking for interviews, I feel I also have to make myself available. I would respond to a high school student working for a school paper, as much I would from a person from the New York Times or Washington Post. I don’t make distinctions. I know that there are people, especially students of non-fiction writing, who want to ask questions because I’m probably part of their classroom discussion.

RK: You don’t use a tape recorder, and you don’t have a cell-phone. But, technology has become a major player in today’s journalism. Do you think advancements in this regard (iphones, twitter, etc) have helped or hurt journalism?

GT: I don’t think it’s helping. It might be hurting it more. I don’t have a cell phone because I don’t want to be walking down the street and have my phone ring and talk to them while I’m on the street. And, I don’t like it when I call someone up and they answer on a cell phone; I can hear the sound of traffic, or they’re doing something else while they’re talking with me. I like direct conversation and I like to do it in person. I don’t like to use the phone. I don’t want to denigrate what I don’t know much about, but what I know about research is that I go to the place, I see them, and I interview them. I can’t imagine getting this information by ‘Googling’ someone. I might Google someone to find out a phone number or something like that but I would never conduct an interview through technology.

RK: So, you hardly use the Internet in preparation for interviews?

GT: Right now I’m doing Joe Girardi. I could go the Internet and find out something about him, but I’m not sure how accurate it is. I would never write about someone I didn’t spend time with. I have to have my own take. I need to look in the eyes of the people. I need to see them in their own setting. When I was doing Joe Girardi, I went to the baseball games, but I also wanted to see him at home. I wanted to meet his children and see him in a non-baseball environment. I like to see natural situations.

This is not easily done and people always wonder, how do I get my foot in the door? You have to develop trust from a young age. When you first approach a stranger, you have to approach them with good manners. My own personal opinion is that you have to look presentable, and dress for the story. I don’t own a pair of blue jeans. I don’t dress down for anybody, I always dress up. I’m always wearing a jacket and a tie and a suit and a hat. I’m dressed up because I think what I’m doing is very important, and I think the people I’m talking to are very important. I wear the same thing if I’m going to a wedding, Bar Mitzvah, a funeral: it’s shows respect to the other people that are there. Ever since I was a cub reporter at the New York Times I’ve always done that. I see reporters in the press box, and they’re dressed very casually. They look comfortable, but I don’t think you should be dressed like you’re going to a tailgate party. I think it’s disrespectful. I even dress up for construction workers, as if I was interviewing the Mayor of New York.

RK: You have a well-defined writing and researching philosophy. Do you have a more general, every day, philosophy you live by?

GT: I only had one full time job my whole life, that was at the New York Times. It only lasted ten years. I started as a copy boy in 1953, I went in the army and came back in 1956, and then worked until 1965. I’m now 80. I haven’t had a full time job since 1965. But, what I always had was a belief that what whatever I did, I wanted it to be worthy of being read after I died. That’s something of a religious nature. Religion is really about life in the here and hereafter. I think that good work has to have a life after death. The great composers, like Beethoven, or the modern songwriters, like Gershwin, their work has lived beyond their lives. That’s like religion. People seek to live the good life, but have a life after death. That’s religion and it’s also art. Whether it’s a great violin player, or soprano, or a singer like Sinatra, they live after they’re dead. Great actors are still alive, you see their films.

RK: So you don’t ascribe to a particular religion?

GT: I was reared a Catholic, but I’m not a church going Catholic. I do respect religion, and I’m now learning a little bit about Christian’s who are born again. One of them is Joe Girardi. They are very religious, and Christian people. As I speak to you now there is a basketball player who’s very Christian, Jeremy Lin. There’s

Tim Tebow from the Denver Bronco’s. And, Ray Lewis of the Baltimore Ravens. Religion means a lot to all kinds of people. I find that very endearing for people to have faith. Sometimes they’re down on their luck, and they’re depressed about it, and they look to their faith and see it as the will of God, and there’s a lesson for them. If you have it, it’s a very enhancing, and fortifying quality to imbue. You have something within yourself that gives you strength when you feel you’re at your weak moment.

RK: If you could choose one person, dead or alive, that you could write a feature on, who would it be and why?

GT: (pauses) There’s so many people. Let’s see. I could take a person like Fidel Castro – forget the politics – and just as a man he would have been a great subject. If I could have hung out with Castro when he was younger, it would have been better.

If I were to go now to Russia and to do Vladimir Putin, that is something I would like to do. Putin is a great character.

RK: Any historical figures that you would have loved the chance to interview?

GT: The great people who shaped the world like Mao Zedong. Hanging around Mao would have been something. Or, Nathaniel Hawthorne, or F. Scott Fitzgerald. Even today there are people I wish I knew better like Madonna. She’s had such a long history as a performer and I don’t know anything about her. I know a little bit about Lady Gaga. I was in her presence a few times writing the Tony Bennett piece. She’s a more interesting person than anything I’ve read about her.

There’s so many people I wish I knew. And, there’s so many people I wrote about I wish I could have spent more time with like Joe DiMaggio.

RK: Having spent so much of your life examining people, and human behaviour, are there any general comments you can make on the commonality of human nature?

GT: I’m reading a wonderful book by the great actor Frank Langella. It’s not going to be published for two months. It’s about famous people. He knew so many famous people. He knew Paul Newman and Charlton Heston. He knew so many people. If you read this wonderful book called, Drop Names: Famous people as I knew them – it sounds like I’m plugging this book, and I guess I am. To read this book is to read about people we all know because they’re so famous but the way he writes about them you learn things you never knew. You often learn that they didn’t know that much about themselves. So, the projected image they’ve managed to distribute to the world is not necessarily who they are, but who they would have you believe they are. He knew these people because he worked as an actor with them, he had an insight because he spent time with them on equal terms. He wasn’t a reporter with a pad and pencil. I realized that what you think you have isn’t what you have. What you have is what they choose to give you. If you spend enough time there’s an entirely different character behind the character. It’s like the Wizard of Oz. Behind every rambunctious person is often someone timid. There are so many variations on the theme of fame, and what’s behind the personality. These are forces you have to explore deeply to get to the truth of that force. People are so many people within people. Whether people are famous or not, there’s always a story there.

RK: When Hollywood eventually makes your biopic, who would you like to play you?

GT: Well, I can’t imagine who would be like me. It depends on what age I’m at. If I wanted to have a good actor, a wonderful actor, it would be Stanley Tucci. I think he’s one of the great versatile actors. Look at Frank Langela, he is someone I would also like. He’s such a great performer.

RK: When Gay Talese has a cold, how does that transform the world around him?

GT: Fortunately, it doesn’t affect the ones around me because I don’t have to sing. If I have the flu I can’t do my work because it involves going outside. I want to see. I can’t do my work over the phone or Internet. It’s like being a performing athlete. I am a performer, a performing writer. I have to be in condition. I go to a gym to stay in shape, and do the best I can with my 80-year-old body, and it moves around pretty well.

For more on Gay Talese:

1) Visit his website www.gaytalese.com

Generally I don’t learn post on blogs, even so I wish to say that this write-up extremely pressured me to try and do it! Your writing taste has been surprised me. Thank you, quite wonderful article.

Hello there, just became aware of your blog via Google, and identified that it truly is truly informative. I am going to watch out for brussels. I will appreciate in the event you continue this in future. Lots of men and women is going to be benefited from your writing. Cheers!

This is great! An associate shared this with me this morning on Twitter. Impressive.