“If I don’t stand and fight for change, then I’m part of the tyranny that’s taking place. I refuse to succumb to being a second class citizen…You can’t whitewash what God has planned for me in my life.”

The separation of sports and politics is a widely accepted norm. But some athletes refuse to play by these rules. John Carlos is one of the brave few, and he’s paid a heavy price for using sports as a platform to demand racial equality.

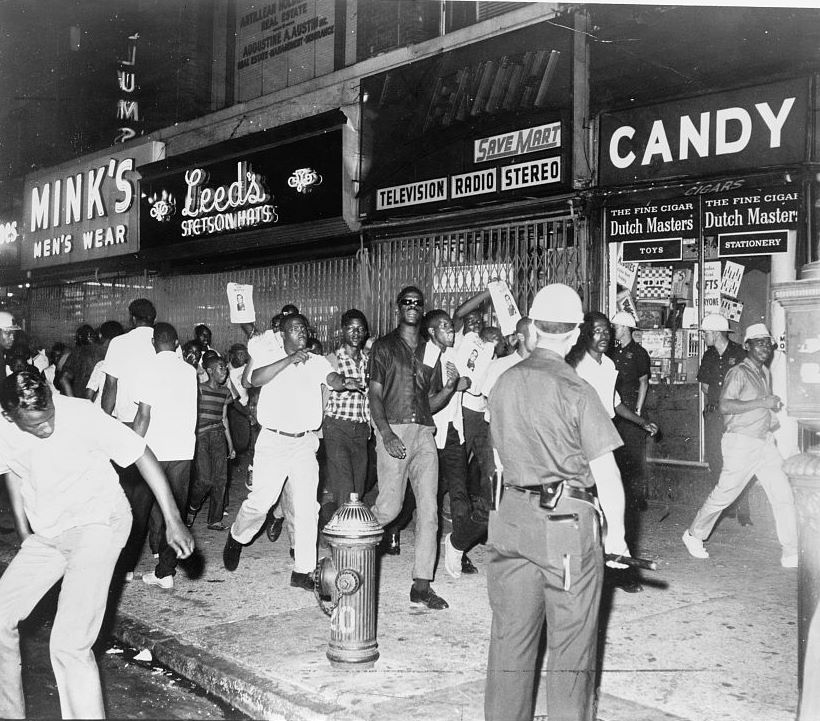

Born in Harlem, New York in 1945 Carlos was blessed with a natural sporting ability. Despite his amazing athleticism – he virtually could have succeeded at any sport – his career has been defined by struggle: The struggle to be accepted, the struggle to make ends meet, the struggle to stand up for black/human rights, and the struggle to survive when it felt like the whole world was against him.

Yes, on paper, Carlos has a fantastic sporting career: He’s won Olympic medals for running, he’s played in the NFL and CFL, and he very well could have been a professional boxer or swimmer. All that, however, will remain as merely a footnote in his history because John Carlos was born at a time of extreme racial segregation in the United States, and instead of accepting the system, he fought to change it.

and CFL, and he very well could have been a professional boxer or swimmer. All that, however, will remain as merely a footnote in his history because John Carlos was born at a time of extreme racial segregation in the United States, and instead of accepting the system, he fought to change it.

Before Carlos made history, his life set him on a crash course to athletic activism. His childhood in Harlem exposed him to racial oppression in America; he experienced nasty racism, but found clever ways to demand and achieve dignity. As a teenager he learned of his ability to run extremely fast by stealing from trains and delivering food and clothes to his poor community; he considered himself the local Robin Hood.

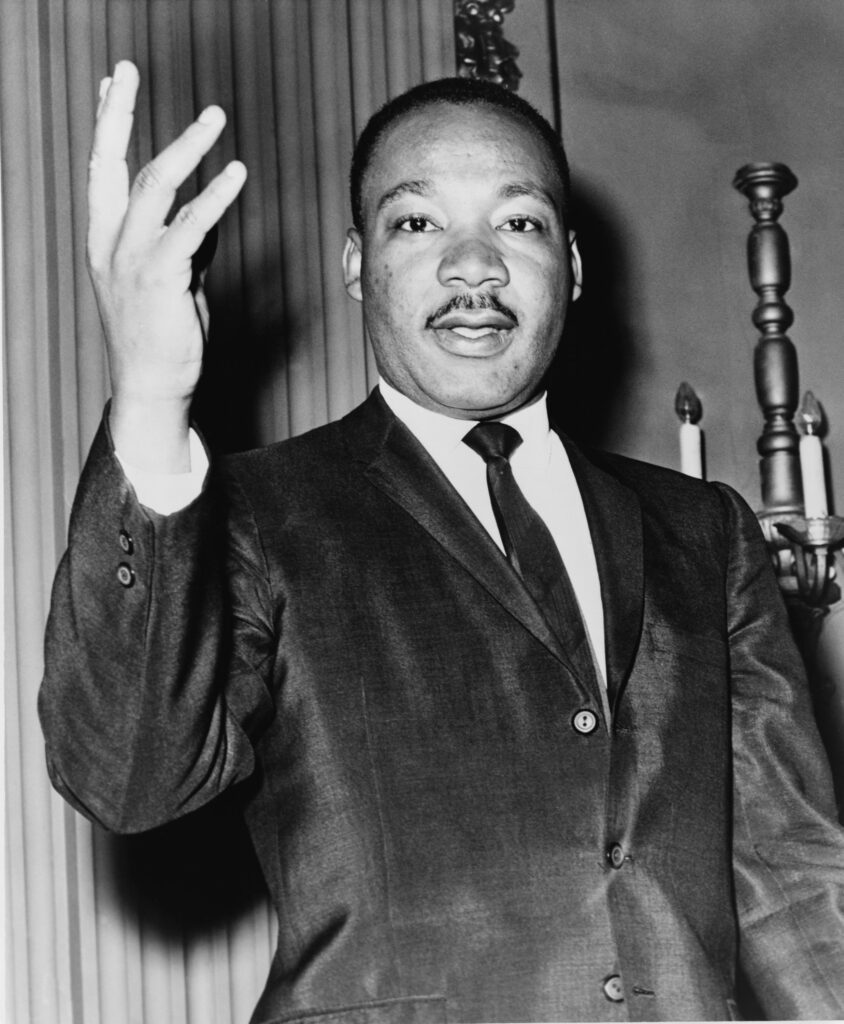

Not only was Carlos discovering that you had to stand up for yourself to get respect, he was fortunate enough to be educated by some of the most influential black activists in history. As a young man, he had the opportunity to hang around and learn from both Malcolm X and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. John Carlos’ upbringing prepared him to use his athletic prowess to do something important. And, that’s exactly what he did.

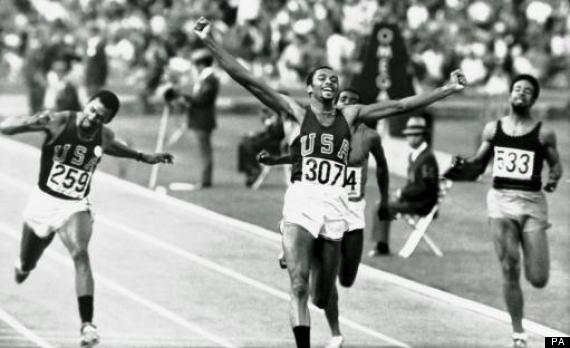

It was 1968 at the summer Olympics in Mexico City. John Carlos was at the height of his athletic career. He was, at that time, considered to be one of the fastest men in the world. He had dreamt his whole life of running at the olympics – it was the pinnacle of success for any athlete – and he was finally there.

He was victorious: in the 200m sprint he claimed the bronze medal, while his teammate, Tommie Smith, took the gold. As Carlos and Smith stood on the podium to collect their medals it should have been a time of great celebration and excitement. But instead, they used this moment in front of the world to make a deafening statement: in silence, with their heads bowed, they raised their black-gloved fists in the air to protest the extreme amount of racism in America.

The symbolism of the moment is complex and highly misunderstood. 1) The black fists in the air didn’t represent black power but human rights; the clenched fist stood for unity and not aggression, 2) they wore no socks to represent the poverty amongst black communities in America, and 3) they wore beads around their necks to protest lynching.

The moment on that podium was a twist of fate. Leading up to the games, Carlos and Smith had been seminal members of the Olympic Project for Human Rights (OPHR). The goal of this organization was to “expose how the United States used black athletes to project a lie about race relations both at home and internationally”. Their plan was to encourage all black athletes to boycott the Olympic games because, as their mission statement said, “why should we run in Mexico only to walk home?” To avoid the boycott they had three demands: 1) exclude apartheid South Africa and Rhodesia from the games, 2) restore Muhammad Ali’s heavyweight boxing title, and 3) remove the overtly racist Avery Brundage as the head of the International Olympic Committee. The project crumbled when Dr. Martin Luther King, who had backed the movement was assassinated, and South Africa and Rhodesia, on a separate occasion, were disinvited to the games. With the backbone of the movement in shambles the athletes decided to go. This set Carlos and Smith up for their opportunity on the podium.

The backlash for the podium protest was immediate. Before the national anthem had stopped playing the crowd of over 50,000 began to reign down boos, and things were thrown at the athletes as they left the field. From that moment things spiralled into chaos: Carlos and Smith were kicked out of the Olympic village, the international media sharply criticized their actions, they received death threats, and their loved ones were thrust into a hateful limelight.

These days, Carlos and Smith are hailed by many activists and athletes as heroes. Their courageous stand in Mexico is remembered as a triumphant moment in American history. They’ve won awards for their activism, and continue to thrill crowds around the world with their story.

In 2011, John Carlos along with sports writer Dave Zirin, captured the moment and the history in the book The John Carlos Story: The sports moment that changed the world. Although the book details how John Carlos was a part of history and even, to a degree, changed history, it expresses clearly that he continues the struggle for racial equality to this day. Progress has been made, but the race is not yet won.

There is much I WANNA KNOW about John Carlos’ struggle for equality.

I caught up with him from his home in California.

From the 1968 Olympics, to growing up in Harlem, to Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, to politics and sports, we cover it all.

Ryan Kohls: Long before 1968, you had a vision about what was to come. Can you tell me about that?

John Carlos: I must have been about seven or eight years old. Early one morning, my walls just lit up like a big screen, right across my wall. It showed me in a forum where there was a whole bunch of people, and I was standing on a box. Everybody was excited and happy. By the time it dawned on me that I was the one they were applauding for I raised my hand to wave. It was like someone snapped their finger and all the sunshine and joy and happiness that was around me turned to anger and venom, to the point where they started throwing things, using bad language, and spitting at me. It scared me so bad, and the whole day I was in a state of shock.

I recall going to dinner that night and I remember my Dad asking, “What’s wrong?” I said, “Dad, I was in a movie. Everyone was happy about something I did then they got mad at me.” My father looked at my mother as he was embracing me, and said to her, “Looks like God has something special for this kid. We’ll have to wait and see what it is.”

Fifteen years later I’m on that victory stand and exactly what happened in that vision happened in that stadium.

RK: I want to get back to that moment, but before that I want to talk more about your upbringing. How did growing up in Harlem in the 1950s and 1960s shape your education of racism in America?

JC: I would have to say it probably started in the late 40s. By the time I was five years old and running around my fathers store, I was noticing who was in the environment I grew up in. In my estimation it was like a soup bowl, everybody was there: there was white people, black people, hispanic people. By the time I hit 7, I recall standing in my father’s doorway one time and I saw two winos, one black and one white. They were out partying that Friday night and were now lying on the ground. On Saturday a young white cop came up to them laying on the ground, and when he went to the white fellow, he banged his stick on the ground and the guy didn’t move, so he poked him, and told him to move on. Then he moved over to the black guy, in my head I thought I was going to see the same thing again. He tapped the stick on the ground, and the guy didn’t move, so he went down to his feet and took the nightstick like it was a baseball bat and wore the bottom of this guys shoes out. I saw this guy levitate off the ground and lay in a horizontal position, and he almost got killed trying to run across the street. It put me into shock. I think that was the first time that I ever saw any race relations, not knowing it was classified as that. I asked my father, “Why did he do that?” He said, “All people are not treated the same in this life we live.” I think that subconsciously triggered my mind to start looking for the differences from that experience there.

RK: The hardships of your early life in Harlem led you to a phase in your life you refer to as the “Robin Hood” days, when you and your crew stole from trains and brought the goods back to the community. Do you think the ends justified the means in those days?

JC: I think it was something that was necessary to do. Robin Hood was a guy that impressed me because he realized there were two laws of the land: the Sheriff of Nottingham’s (Man’s Law) and God’s law. He chose to realize that God put this land here for all its inheritants. Those who were less fortunate didn’t know how to take care of themselves. Robin Hood took it upon himself to say I’m not concerned about man’s law and repercussions, I’m concerned about those who are less fortunate. In my mind, people who might have been living in low-income communities and ghettos would fall in love with Robin Hood.

I took it to the next level though when drugs came into the neighbourhood. They used to have a thing called King Kong liquor (bootleg liquor). You can equate that to PCP; you drink that liquor and go to the roof thinking you can fly, then jump to your death. I went to bed one night and King Kong was gone and heroin was the drug of choice out of nowhere. Many individual’s parents were disillusioned and many fathers became missing in action. There were many mothers raising kids on their own, plus they had their own vices. There was no food in the ice box – remember we didn’t have any fridges. And, a lot of them didn’t have clothes. So, these freight trains were coming in near Yankee Stadium everyday. Me and my partners went over there to explore what these trains were carrying. We started breaking in and realized they had clothes, frozen foods, and goods that people in the community needed real bad. I remember telling my buddies at the time that we weren’t going in there for our own self-interest. I remember one of them said to me, “We’re going to be rich!” I said, “No. This ain’t for our pockets, this is to help the people in our community.” They got into it as much as I did just to see the smile on somebody’s face when you give them something.

RK: Before you became an influential individual, you were influenced by some of the most revered thinkers in modern times: Malcolm X and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. First, what was it about Malcolm X that captivated your imagination as a teenager?

JC: I think first of all it was the vision he had. Before I laid eyes on him I heard him on the radio. He had such a strong emotion and vigor about his delivery in what he was talking about. He was talking about learning your history, respecting yourself, fighting for your environment, educating yourself, and standing up for your rights. These are the types of things I heard as a young individual and I was so encouraged. There wasn’t many talking in that vein, in terms of saying “I am somebody.” I was just impressed that a guy could be on the radio talking that strong, and encouraging black people to start pulling ourselves up by our own bootstraps.

When I went down and had the opportunity to see him I was in a state of shock all over again. I anticipated him being a dark-skinned individual because of how he was talking about black people. But, when I saw him I called him a red-bone. I just had that much more pride in him: I was fair-skinned and he was fair-skinned. There was a connection there. When I saw in person how laid back he was, how self-assertive he was, and how he was trying to bring the people together as a unified race of people, I was enthralled. After the second or third time I saw him speak, I stuck around after and asked him if I could go with him from one location to the next. He asked me why, and I said because I have questions and I want to learn. He smiled – he had this dimple in his chin that I’ll never forget – and said to me, ‘Sure son, you can come with me. Can you keep up?” I didn’t understand what he meant at the time, but when we got out there I realized he was a fast walker.

RK: And, how influential was Dr. King in your life?

JC: He was very influential in terms of what happened in Mexico City. He was like a symbol in my household. My mother and father had the highest level of admiration for Dr. King based on his non-violent activities, and based on his strong voice in terms of standing for those who couldn’t stand for themselves. There was a difference between Dr. King and Malcolm X. Malcolm was more concerned about his people, black people. Whereas Dr. King was more concerned about all people, and had a clear vision of how to reconcile these issues so that we could all prosper in this life.

When I met Dr. King it was a unique situation. I just left East Texas University and I came back to New York. Professor Harry Edwards called me and told me about a meeting. My mother encouraged me to go, and it was in the old Americana Hotel, near the old Madison Square Garden. I felt outta my zone there, and I was nervous. I was feeling like, what I’m doing here? They tried to relax me, and then twenty-five minutes later, Dr. King walked in. That was like God walking into my living room. I didn’t look at him as God, but I looked at him in that sense. In my household my mother used to preach that Dr. King was God’s first lieutenant he sent to this earth. When he entered that room two things jumped on my brain. The first thing was, man my momma need to be here right now – she needs to be a bug on my lapel, or rock in my pocket. The second thing was, wow, I’m in the room with Dr. Marin Luther King.

What I remember most about him that day was how comedic he was. He cracked jokes to relax everyone, and then  we discussed why we all came together. We were there because he had taken a vested interest in the Olympic Boycott. We didn’t know he was going to come out full-blown to support it. He didn’t want to take control, but be second in command. He also said in that meeting that he was sent a bullet in the mail with his name on it. At the end of the meeting he asked if anyone had any questions. I naturally had a few questions. The first one was: Why would you join this movement? Did you even play sports? He said, “I can’t even shoot pool.” I laughed and said, “Why would you get involved?” He said, “John, imagine being in a rowboat and you roll out to the middle of a lake, and you pull the oars in and wait for everything to be still, and you grab a rock and drop it in. What happens?” I said, “It creates vibrations.” He said, “Absolutely, it creates waves. When those waves move out it lets everyone know that something is not right. This boycott is that rock.” That was a powerful statement. He said it will bring attention worldwide about the plight of black people in America with a non-violent statement.

we discussed why we all came together. We were there because he had taken a vested interest in the Olympic Boycott. We didn’t know he was going to come out full-blown to support it. He didn’t want to take control, but be second in command. He also said in that meeting that he was sent a bullet in the mail with his name on it. At the end of the meeting he asked if anyone had any questions. I naturally had a few questions. The first one was: Why would you join this movement? Did you even play sports? He said, “I can’t even shoot pool.” I laughed and said, “Why would you get involved?” He said, “John, imagine being in a rowboat and you roll out to the middle of a lake, and you pull the oars in and wait for everything to be still, and you grab a rock and drop it in. What happens?” I said, “It creates vibrations.” He said, “Absolutely, it creates waves. When those waves move out it lets everyone know that something is not right. This boycott is that rock.” That was a powerful statement. He said it will bring attention worldwide about the plight of black people in America with a non-violent statement.

The second question was, “Why would you go back to Memphis with your life threatened?” He said, “John, I have to go back to Memphis and stand for those who won’t stand for themselves, and those who can’t stand for themselves.” That right then split the pea in my mind that there were people who could but won’t stand, and those that want to but aren’t allowed to. When he said that I felt like my life had come full circle. I’ve always stood for those who wouldn’t or couldn’t stand for themselves.

RK: You were with Dr. King days before he was assassinated. What do you remember about that day you heard he was killed?

JC: First was the hurt and sorrow because he knew he was going to lose his life. At the same time I realized that he made a statement to me that his life was not as important as the job at hand. He said he could die, but he would never die in terms of the spirit in which he stood for. That made me, in Mexico, understand that they could take my life, but not what I stood for and was reaching out to society for. He lived stronger in death than he ever did in life.

RK: At the time of the 1968 Olympics, you were considered one of the fastest men in the world. What’s it like to be able to run that fast?

JC: It’s a blessing by God that you might be the best in any given profession. The blessing, for me, is that I was able to take it and share it with the spectators. I was never a standoffish athlete, saying look what I have and you should envy me. I used to take it in the stands and talk with the people and say, “I’ll be back in 9 seconds,” and then come back and hang out with them. I wanted to give the people a good show for their money. I got that theory from a white fella that used to come to the Savoy Ballroom, Fred Astaire. We used to perform outside and he would flip us a silver dollar, and told us that he did that because we put on a good show.

RK: So, when you got on that podium, did you remember your vision as a child?

JC: I remembered the vision as soon as those people started the booing and chanting. From that point on that vision was on my mind to the point I said, “Oh shit, this is what that vision was about.” The only difference was I had two others on the box with me, and I had to understand what was taking place.

RK: You’ll forever share something with the two other people on that stand. Tommie Smith was your teammate and won the gold. Your relationship after the games, however, suffered. Was it because of all the scrutiny?

JC: It’s not the scrutiny. It’s a situation we had long before Mexico City. Mr. Smith is an introvert, and I’m an extrovert. Yet, God put us in the same venue in the same event. Every athlete wants to be on the top of the hill. I’m willing to share, Mr. Smith wants to be independent. That’s the attitude he has. I tell him we’re joined at the hip – now, you don’t hear about Jekyll without Hyde, or Abbott without Costello, and you don’t hear about Carlos without Smith. He seems to think that he can be independent. We’re still competitive to the point that he said some things in his book that wasn’t so flattering.

RK: What’s your relationship with Tommie like today?

JC: I have nothing but the utmost respect for Mr. Smith.

RK: The other person on the stand was Australian runner, Peter Norman. He took a lot of heat for his participation in that moment. How much did his support mean to you and Tommie?

JC: Peter Norman was a godsend. We could have went through 10 million white individuals, and 9,999,999 would never have attempted that, let alone do it. Peter was like a piece of clairvoyant paper. There was no color with Peter. It was about his spirit, his heart, and his vision of what could happen in society when people come together to do something creative. I’ll always have respect for Peter, more than Tommie, because Peter was genuine from the day we met to the day he died. When you sit back and think about what happened when we left the victory stand and returned to our home countries, there was two individuals in America and one in Australia. If they decided to whip up on John Carlos they would do it until I was tired, then move to Tommie Smith. In Australia – and remember in the late 60s it was parallel to South Africa in terms of its abuse to people of color – Peter Norman stood up and said he believed in justice and equality for all people. When he went back, just because he put a button on his shirt, they beat Peter 24/7. There was no spin-off on Peter. At the same time, the more they beat him the stronger he got to his commitment. He never said one negative thing about us, and stayed strong to his death. He had nervous breakdowns, got into alcohol, his marriage broke down, and they didn’t even acknowledge him at the 2000 Olympic games in Australia. All of these things were taking place, but Peter never changed his views and values, and I’ll always have respect for that long after I leave this world.

RK: Do you think the Olympics salute is still misunderstood as representing black power and not human rights?

JC: You have to take into account that at the time right-wing media was the only media out there. They wanted to make it more of a black power demonstration to intimidate the people. They wanted to bring the end to us by saying that we were a black militant group that was going to come in and blow up the Statue of Liberty and destroy America, which was so far from the truth. Then at the same time, Black people were clinging to it and saying it was. But, if you think about that fist with the glove on. Before it was a fist it was five fingers representing all races – they are all individuals until they unite – and when they become unified they become a powerful force. These things were never revealed, so everyone had their own interpretations from what the right-wing media was putting out there for them to eat.

RK: You detail in the book that the FBI was following you after the Olympics and harassing your then wife with pictures of you with other women. Have you ever received an explanation or apology for that?

JC: (laughs) I don’t think anyone has ever received an explanation or apology from the FBI.

RK: Is that something you want?

JC: Let me just say this. We’re not looking for apologies, we’re looking for justice.

RK: How do you anticipate receiving that justice?

JC: We’re fighting for it, brother. We’re standing tall. It’s like this: If I don’t stand and fight for change, then I’m part of the tyranny that’s taking place. I refuse to succumb to being a second class citizen, and not being able to go the university of my choice, or live in this community. I refuse to always be the

doorman, or the guy who cleans the toilets. You can’t whitewash what God has planned for me in my life.

RK: You talk about God a lot, how would you describe your spirituality? Are you a Christian?

JC: I wouldn’t say I’m Christian. From the time I was a little boy I’ve always gone to religion to fill that void in my life. I was a Catholic, I was a Muslim, I was Protestant. I was all religions. My consensus is that I know there’s a God in the sky, and I relate to God himself. I don’t follow no one religion. I follow my spirituality. Relative to what happened in Mexico, it dawned on me that God had a special plan for me. Not just on that stand, but the way my life was led up that moment, and continues to this day.

RK: People always want to ask you how you think racism in American has changed since 1968. I’ve heard you say that some things certainly have gotten better, but we all know racism is alive and well. Why do you think it has such a stronghold in America?

JC: It has a stronghold in America because we refuse to deal with the race issues. We prefer to sweep it under the carpet instead of putting it on the table and having some serious discussions about what’s going on in this society. Even in the schools he haven’t figured out how to deal with this. Until we start to deal with these issues we are going to be in a position to self-destruct because we can’t deal with the most prevalent thing that’s destroying the society.

RK: Throughout your life you have often told people they had 48 hours to deal with the problem, or you’d do something about it. If you could tell one person that today who would it be and why?

JC: I would probably tell it to the people in the educational system. I think that what happens relative to young individuals, we have the responsible to educate them on the various cultures, ethnicities, and economics we deal with. It’s like, if you have money you have reputation and power. Those that have the power are concerned about the power players. In the election right now with Mr. Romney, he’s dealing with the power brokers and has no concern for those who are less fortunate. How do the power brokers thing they’ll have a good situation if they have people trying to find a job and health care? The society can not continue like this without the bottom falling out. And, where do we get the chance to put this on kid’s minds?–the institution of education.

RK: You spend the bulk of your energy today working with the youth in America. Are you seeing positive signs that the youth are motivated to make a change? Or, do you think this generation is apathetic and doesn’t have the fire your generation had?

JC: I think it’s sporadic. It’s not a steamroller where everyone’s on the same page. When you think about the youth of today, they don’t have the self-knowledge we had in my day. We had a concern about family, education, community, and safety. All of those things are no longer in existence today. They don’t teach kids about values and morals in schools no more.

RK: Do you think the kids today have it too easy?

JC: Our kids don’t get up to turn the channel no more, they sit in a chair and flip the remote. Our kids don’t go to the library and do research, they go and push one button. They’ve made it so simple that kids don’t want to do it. What was the TV originally invented for? It was based on education. Somebody then said, “The hell with education, we’re going to use this shit to make some money.”

RK: At the end of your book, sports writer Dave Zirin challenges the sports world and athletes to become more political. Do you think this needs to happen?

JC: Let me ask you this question. Do you think they’re outside of the human race? No. They come from the same community. Why wouldn’t they have a vested interest in what’s happening morally, and politically? They’ve been co-opted, and we have a tendency to be afraid to offend our oppressors.

RK: Are there any positive examples you’ve seen lately of athletes speaking up for a cause?

JC: I think the Pittsburgh Steeler’s coach Mr. Woodsen is admirable for speaking up about social justice issues.

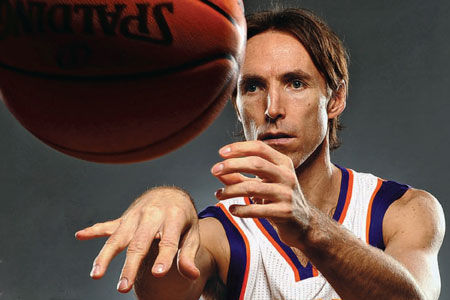

Steve Nash in Phoenix. He has a concern for the hispanic people down there. He’s an individual who grew up in apartheid South Africa, and then left for Canada. Based on him dealing with those issues, he has no reservations about his vision for society. He’s not afraid to stand up and speak on the issues. Do other athletes have the tenacity to do this? Only time will tell. You may have your 15 minutes in the bubble as a professional athlete, but your mom isn’t in there with you, and your community isn’t either. I chose not to walk away from society. Muhammad Ali, Jackie Robinson, and many others did the same thing, and said, “Hey, I’m a sportsman, but I’m a human being first.”

RK: What musical artists have provided the soundtrack for your life of triumph and tragedy?

JC: I got so many of them and most of them are in the jazz field. Thelonious Monk, Miles David. Max Roach was my man. Nina Simone, Ella Fitzgerald, James Brown. It’s a collage of them. I’m into the old school.

RK: In your teens you were on your way to becoming a professional boxer until your mother discouraged you from fighting. Do you think if you would have pursued it further you could have beaten George Foreman?

JC: I used to tell people who George and I should fight in an exhibition match. People would always tell me George would kill me in the ring. I’d say, “That’s your opinion. My opinion is that he’d have to catch me first.” That was one of my ambitions to become a boxer. I used to tell my mother I didn’t want to box as much as I wanted to make a million dollars. I told my mom I’d be alright. All I wanted was some start-up capital and that was the quickest way to do it. My idea as a youngster was to take care of my family and make sure they were secure. My mom stopped that and tried to protect me. She said, “Johnny, I’m afraid it’ll break your face up and hurt you.”

RK: In the book there’s a quote: “the fight for social justice is a marathon and not a sprint.” Do you have hope that the marathon will end one day?

JC: They say the Lord will come back, so I think when He comes back we will see love and harmony between all the people on this planet.

For more information on John Carlos:

1) visit his website: http://www.johncarlos68.com/

The photograph on your page above captioned with ‘Norman’ misidentifies Larry Questad, the third place US qualifier in the 200m for the 1968 Olympics at the Tahoe trials, as Australian Peter Norman.

Thank you. It’s been corrected.