“Poverty is no longer the number one challenge to Africa; it is inequality. This is the most deadly issue facing African countries because it is so easily politicized, ethnicized, and very easily militarized.”

John Githongo is a man you need to know about.

In my opinion, he is an African hero who is doing work essential for the future success of the continent.

Corruption is a big problem for many countries. In Kenya, it is astronomical; some estimates predict that Kenya loses up to 1 billion US dollars a year to corruption.

John Githongo has made it his life’s mission to try and change this.

Let me see if I can sum up, as briefly as possible, what John Githongo has done:

- As the head of Transparency International in Kenya – a civil society organization dedicated to the fight against corruption – John began a career of anti-corruption work.

- In 2003, after being appointed as the permanent secretary of governance and ethics in the Kenyan government, John began to uncover and expose the mass amounts of corruption being carried out by the countries elite.

- Ironically, he was hired to do just that, but shocked his superiors by exposing them.

- Following multiple death threats John left Kenya, and went into exile in the UK.

- In 2008 he returned, and under the protection of the state, has continued his fight against corruption.

In 2009, famed journalist turned author Michela Wrong documented John’s story in the best-seller, It’s our turn to eat: The story of a Kenyan Whistleblower. The book has helped to get John’s story out to a global audience.

In the book, John Githongo’s story reads like the script of a Hollywood suspense/action flick. Lucky for us it’s not fiction, and John Githongo’s fight continues to this day.

There is much I WANNA KNOW about John’s struggle against corruption, and I was blessed to speak with him for about an hour.

Below is the transcript (with some audio-clips) of the interview I conducted with John via skype.

From corruption, to poverty, to Kenya’s potential for revolution, we cover it all.

Ryan Kohls: Although perhaps a simple question, maybe it’s best to start by asking, what is corruption? How would you define it?

John Githongo: Corruption is, by general description, the abuse of vested authority for private gain. For example, that can be a public official abusing that authority, or a private official. It’s a rather dry description, and it’s only once you get anecdotal with corruption that it becomes interesting.

[soundcloud width=”100%” height=”81″ params=”” url=”http://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/15917890″]

RK: When did you begin your interest in combating corruption?

JG: For me, I sort of slid into it to be honest. My father was one of the founder’s of Transparency International. He was involved with that organization in the early 90s. At the time I was quite skeptical about starting a non-governmental organization to fight corruption, but I got more involved as I watched what was happening in Africa.

It was around this time that there were a large number of democratic transitions taking place. Very high levels of corruption unfortunately accompanied these transitions because politicians needed to mobilize resources to finance the elections.

When the Berlin Wall fell everyone was talking about good governance and anti-corruption. That found me at a time when I had started researching, and writing about corruption. So it was a whole sort of coincidence of factors that led me to it.

RK: In Michela Wrong’s book, It’s our turn to eat, she begins by telling the story of you wearing a wire into a government meeting, and how the tape began playing back. Can you describe the intensity of those days when you were wearing a wire, and had to live so secretly?

JG: I was appointed to the government when they had just won an election with an almost 70% majority. We were seeing the end of one of the most corrupt, kleptocratic regimes in the history of Kenya (Daniel Arap Moi). The level of optimism was so high. Kenyans were polled as one of the most optimistic in the world. Third, I think. That was in early 2003. That informs the whole atmosphere in which I went into office; anything was possible.

One of my early problems in government was that ordinary Kenyans were arresting policemen for corruption! That was an incredible, exciting time.

Yes, life was extremely intense. The key thing is that I had to get accustomed to the fact that you lose your personal life. You make enemies, a lot of them. That I had prepared myself for, but I felt that I had the President’s backing in the fight against corruption, and only when I realized I did not have that did things get intense.

RK: Following your exposure of corruption high up in the Kenyan government, you went into exile in the UK. How fearful were you before you left?

JG: I was told directly that what I was doing was going to lead to my death and that it would be done by any means necessary. To be very honest I had prepared for some time to go to Oxford, so it wasn’t as if it was a sudden decision, but a realization that I had pushed a lot of buttons and the time had come for me to make my move.

RK: You returned home to Kenya in 2008, what is your security situation like now? How has Kenya changed?

JG: My security situation was radically altered as a result of the coalition government. The Prime Minister (Raila Odinga) gave his assurance of my protection.

My general perception since coming home is that Kenyans are much more insecure as a people than before I left.

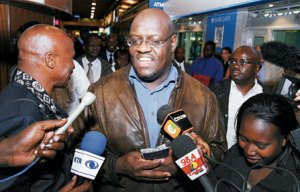

Githongo returns from exile. Nairobi airport. |

|

RK: You’re back in Kenya, yet some of the people you exposed for corruption are still leaders in the government. How awkward is that?

JG: It’s uncomfortable, but more uncomfortable for them. That’s life though. I have met, and sat in the same meetings with some of them. We pretend as if nothing happened.

My opponents are still here. Had they had their way in 2007 I probably wouldn’t have been able to come home. They got it wrong, Kenya almost descended into civil war, and that can be a humbling experience for even the most corrupt individuals.

RK: In today’s Daily Nation the top story was entitled “Rising graft mars a strong economy.” The paper is reporting that the number of corruption cases in Kenya are increasing, yet the economy continues to grow. What’s more important to you, fighting corruption or dealing with development?

JG: You have to fight corruption, but you of course have to do all it takes to work on development. What happens is this: you can have rapid economic growth and corruption co-exist very happily. You have seen this in many parts of Africa, and Asia as well. When you have that situation however, you must, as an administration, be prepared to mitigate the inequalities.

Corruption necessarily leads to inequalities, especially when accompanied with high growth because it means they are making money. But if they are making money on ethnic relationships, the government becomes exclusive. A small elite is crewing to a small group of people. In a country like ours where you have political mobilization along ethnic lines it usually means that the inequalities begin to take an ethnic flavor. It is much more difficult to politicize poverty than it is to politicize inequality. Nothing produces inequality more efficiently than corruption.

Poverty is no longer the number one challenge to Africa, it is inequality. It is the most deadly issue facing African countries because it is so easily politicized, ethnicized, and very easily militarized and can lead to very unstable situations.

Look across North Africa (Egypt, Tunisian, Libya) where some of the tumultuous situations have been unfolding. Many of these countries have been doing quite well in terms of growth and on the human development index, but a combination of stark inequalities, corruption, and conspicuous consumption mixed with youthful population leads to the instability we have seen.

JG: Civil society in Kenya since the elections is a lot more fragmented than Northern Africa. What happened in Egypt takes time and organization.

There are too many externalities buffering us right now: oil prices, food prices, and the international court cases. How it would be expressed in Kenya would be different. Things are bubbling though. Revolutions don’t always look the same, and some are messier than others.

RK: Transparency international continues to place Kenya very low on its list – in 2010 it ranked 154 out of 178 countries – are you disappointed with Kenya’s progress in the fight against corruption?

JG: Yes. I am very disappointed that we are still way down there. We have regressed fairly dramatically. We have become a more corrupt country, and I don’t think it’s sustainable in a high growth country. The majority of the population is being pauperized by a variety of internal and external actions, and this can lead to state failure if we are not careful.

RK: I was just in Kenya, and I feel that the police act as one of the biggest contributor’s to corruption in Kenya. Would you agree with this?

JG: I wouldn’t disagree, however, the thing I point out is that in any developing country where corruption is systematic the most corrupt institution is always the police. Why? Because it’s where the people meet the government. The face of the government is the police. When you visit you most likely will not have the chance to sit down with the Minister of Agriculture, but you most certainly will bump into some policemen.

RK: Would making changes at the top of the government filter down to the police?

JG: You have to make changes at the top, yes. But to have real change it must be driven by the bottom with ordinary people basically saying, “we’ve had enough”, and agreeing to change their system of values.

RK: How well are journalists performing in keeping the Kenyan government accountable?

JG: I think they are doing a good job. Unfortunately, the fragmentation in our society and in our institutions (church, state, etc.) is also reflected in the media.

RK: What role do you think international aid is playing for corruption in Kenya?

JG: A lot of aid has been channeled into the fight against corruption. The challenge, when you have a sophisticated elite like in Kenya, is for the donor community to not unwittingly get sucked into this, and become part of the architecture of corruption.

No country ever became a developed country with aid, so we have to be very careful. I always say the first rule of aid is “do no harm.”

RK: What hopes do you have for the future of Kenya?

JG: When I came back I saw that the software of Kenya had failed, but the hardware was working. I use that to describe a situation where we have rapid economic growth, rising rates of primary school enrolment, big infrastructure projects, but high levels of corruption tolerated by the leadership. It’s like putting Windows 95 onto a brand new computer, and we then face the blue screen of death: it won’t work.

I would like to see Kenya going someway down the road of implementing the new constitution. I would like to see efforts being made bearing fruits of reconciliation between the different communities. The fundamental ethnical inequalities need to be dealt with. They are the core problems of inequality in Kenya. We have to deal with historical injustices in a transparent, just manner, or we will break out into war just like in the Ivory Coast.

Kenyan Prime Minister Raila Odinga and John during a press conference to mark his return to Kenya. |

|

RK: What do you think of Paul Kagame’s government in Rwanda? Corruption levels are very low, but democracy is essentially nil at this point in time. How do you reconcile the two?

JG: I think the story of Rwanda is special. This is a country that had genocide, a million people died. It is is the product of a tremendous horror. Within the next five or so years you will have a majority population who cannot remember the genocide first hand, and at that time perhaps the push for democracy will become more urgent.

RK: When I spoke with Jeff Koinange I asked him this question, and I wanted to get your take as well. Other than corruption, is there anything worse than being stuck in traffic on Thika road?

JG: There aren’t many worse things that one can imagine than being stuck in a traffic jam on Thika road on a Friday evening. It is something quite special.

[soundcloud width=”100%” height=”81″ params=”” url=”http://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/15920114″]

JG: It’s a very special place. I describe Canada as the US in terms of size, and development but with Scandinavian values. People are quite laid back and tolerant. It’s big and strong, but it doesn’t push its weight around.

For more information on John Githongo:

1) follow him on twitter @johngithongo

2) Read Michela Wrong’s book “It’s Our Turn To Eat: The story of a Kenyan Whistleblower”

3) Check out his latest project, Inuka. http://www.nisisikenya.com/

0 Comments