“I think some of us feel there are stories that need to be told. That’s who we are and what we do. We just are compelled to do that. It may not make sense or be logical.”

Don’t ever call Steve McCurry a one-photo wonder.

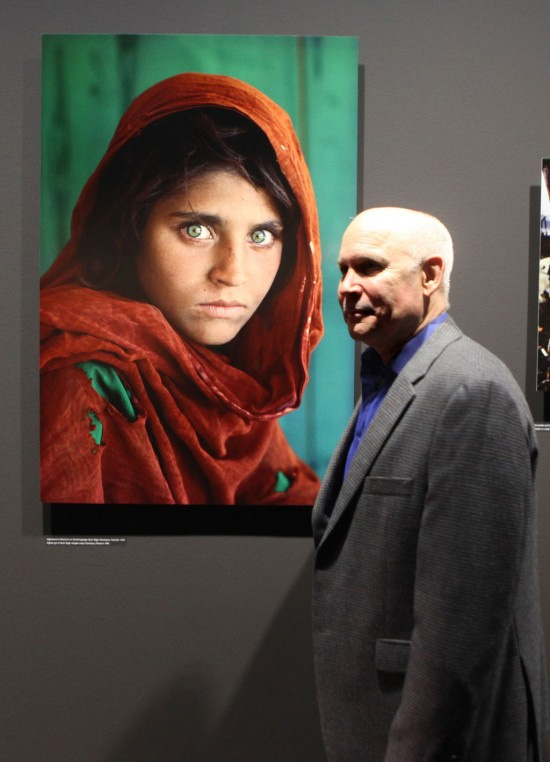

Yes, his haunting photo, famously known as “Afghan Girl”, is iconic. Most people I ask don’t know his name, but they certainly know this picture. It graced the June 1985 cover of National Geographic and became one of the magazine’s most popular issues. The picture of the “Afghan Girl” — whose real name is Sharbat Gula — captured something profound about the refugee experience; the sorrow felt in her piercing green eyes, the tattered clothes of someone on the run, with nothing. The picture cemented McCurry’s legendary status in the photography world, but it is only a glimmer in his illustrious career.

For more than three decades, McCurry has steadily produced some of the most colorful and cinematic travel photography in the world. Working predominantly with National Geographic, McCurry has photographed on six continents and countless countries. Antarctica is the only continent he hasn’t captured. His lens really has seen it all: remote tribes in Ethiopia, Mujahideen in Afghanistan, monks in China, supermodels in Rio De Janeiro.

For his work, he’s won numerous of prestigious awards, including the Robert Capa Gold Medal, the National Press photographers Awards, and four first prize awards from the World Press Photo contest.

McCurry’s speciality is portraits. Below is a perfect example. It has all the hallmarks of his work: lush textures and vibrant colors and the ability to capture the mood of the subject and set the scene:

Although McCurry’s work has now far surpassed the “Afghan Girl”, he still remains in constant contact with her. He even returned to Afghanistan to find her, and photograph her again, in 2002. The success of the photo, thankfully, has impacted her life as well; McCurry helped buy her a house and National Geographic has ensured she remains compensated for the photo’s success.

I caught up with Steve McCurry from his studios in New York City. There is much I WANNA KNOW about one of the world’s most prolific, and popular, photographers.

From the Afghan Girl, to ISIS, to lessons learned from all his travelling, we cover it all.

* * *

I read you’ve traveled so much that you’ve used up 20 passports. Is that true?

(laughs) Yeah. That’s probably accurate.

Your bio says you’ve photographed on six continents. Is Antarctica the only continent you’ve never visited? Would you like to?

Yes. That’s right. It would be interesting to go there. Maybe one day. it’s not on my immediate list. But it’s a possibility.

I feel like you shy away from being labelled a journalist.

I’ve worked for magazines for many years. I don’t shy away from the term being a “journalist” or a “documentary photographer.” I do less magazine work then I did earlier, but it’s something which has been apart of my career.

But would you be more comfortable being labelled as an explorer and historian?

Well, there’s a couple explorers I’ve been fascinated with. I would say, Richard Burton, was a big kind of person I read a lot of biographies about. He’s a fascinating figure from travel. You know I’m talking about Richard Burton the explorer? Not the actor, right?[/answer]

Yeah, I figured. So where did that sense of adventure, exploration come from?

Well, I went to Europe when I was 19, just to travel. Just to do something different and have an adventure. Spending that year in Europe, I decided this was really the best way to spend my time and my life. Travelling, seeing new places, the world, what could be more fulfilling? So, you know, I did that. That was prior to being a photographer. I started thinking about filmmaking. From filmmaking, I studied a bit of photography. I got a camera and decided this was better suited to my personality and the way I would prefer to photograph than make films.

I spent a few years at a newspaper, but my real ambition was to work and travel around the world.

Was there anyone in your family that inspired you to live that kind of life and be a photographer?

Not really. I would say not. My father was interested a bit in photography. My uncle had a dark room. There was some level of interest in photography in my family. But nothing close to what I do now.

You said, “It’s never about the adrenaline. It’s about the story.” So, why do you care about the story? Where does that come from?

Well, I think we’re all interested in human stories, and humanity. You turn on the news and you want to know what’s happening to people, our fellow citizens, and people in other countries. I think that some people dig into it a bit deeper. Do you listen to music?

Yeah, I love music.

You listen to music. There are some people who love music but they’re not compelled to be a musician and practice for hours a day. You love music. You have a sound system, but you’re not a musician. A lot of people have guitars, pianos in their homes. Now and then they pick it up and play. I think your average person wouldn’t be practising for hours a day.

You were a war photographer, rushed to ground zero on 9/11. You’re also the recipient of the Robert Capa Gold Medal Award (for courage). Robert Capa died stepping on a landmine in Japan. Where did that willingness to take a risk come from?

I think I was always willing to take risks and to push the boundaries. It was gutsy going in on the first wave of Normandy. That was a gutsy thing. I think the thing in Japan, when (Robert Capa) was killed. I don’t think in a million years he thought he’d step on a landmine. I don’t think there was a huge risk factor. But he was killed. I think we all try to stay in a margin of safety. You can get killed crossing the street. There’s a million ways. But, I think some of us feel there are stories that need to be told. that’s who we are and what we do. We just are compelled to do that. It may not make sense, or be logical. But you know there’s different types of people in the world.

Have you scaled back from dangerous photography on purpose? Do you miss those days?

Well, I never considered myself a war photographer. I photographed several conflicts, civil wars. I think we all want to have a full life. I think if you look at life as a big smorgasbord, you wouldn’t want to sit and eat one thing. I think you’d want a variety. The world is full of different cultures, regions. There’s a lot to see and experience. It’s all good. I only live once. If I could come back, I could do one thing. But you want to have a variety. It would be a shame not to have a full life. To go to the places you dream about, you want to go to. That seems more sensible. Not just, “I had this label”. I’m only going to do one thing, beat one note.

God bless the person that wants to do that. For me, it makes more sense to sample and experiment with different things in life.

Several of the places you’ve photographed are back in the news, like Yemen. Do you have any compulsion to go back there and photograph what’s going on?

I’d love to go back to Yemen. Is it safe? Let me think….no. I’m not going to go back to Yemen. I think there’s a long list I want to go to. Going back to Yemen is fairly far down on that list. To go back to places you’ve been in the past in fun, but usually it’s a disappointment. It’s never the same, it’s always changed. I’ve been to India 80 or 90 times.

You got your break as a photographer taking a risk going into Afghanistan with the Taliban. I’m just wondering if you’re still game for those kind of assignments. For example, If you were offered a chance to photograph ISIS, would you?

Um, no. I can’t imagine anybody wanting to do that. Well, I can imagine someone wanting to, it’s just not me. If you were given some kind of assurances you wouldn’t be beheaded, sure maybe. There’s probably hundreds of photographers that would be ahead of the line. It’s such a wild hypothetical.

You have a huge connection with the Islamic world. You’ve travelled extensively throughout it and spoken with countless Muslims. What do you think about Islam as a religion?

Well, I think that there’s a lot of different approaches. There’s a lot of different schools of thought. People practice it in different ways. I guess there’s a struggle, people jockeying for position to become the dominant voice of Islam. You know, we’ll have to wait and see what happens. There’s extremists, there’s moderates. But I don’t know. We’ll wait and see what happens in the future.

I would argue there’s still so much ignorance about Islam in America. This debate around it continues to permeate the news. Do you encounter any of the ignorance when you’re in America? If so, how do you counter it?

Most people, I don’t think, are thinking about Islam. They are thinking about March Madness. That’s what people are more passionate about. We all know about ISIS, but that’s over there. The one thing that’s of immediate concern is that baseball season just started. I mean, c’mon man. Let’s get our priorities right here!

You’re not a Yankees fan are you?

Well, I’m being stupidly facetious. You probably thought I was serious. I’m not a fan. I don’t follow sports. I travel so much. I watch the occasional game, but that’s about as far as I go.

In America, 60 percent of people don’t have a passport. Which is perfectly fine. We have enough things going on here. If you want to go on a wonderful vacation, you can go to national parks, you can do to Florida. There’s 100s of places to go to.

Some people have no desire to travel and experience other cultures. You have perspective, through travelling, that most people will never have. How important is traveling for breaking ignorance and living a full life?

Here’s the reality. You think people should travel. But the reality is people have their families. They work hard. On the weekend, they come home and they want to have some joy in their lives. Things like elephants, polar bears, tigers, we all weep for these things, but at the end of the day, there’s just not enough time or money. We all know how grotesque and evil ISIS is but we are all busy. We’re all busy with trying to raise our children, pay the mortgage. We have an illness, or something. But maybe in kind of a cosmic sense, we want this planet to survive in its best possible way, but maybe we’re just a speck hurling through space.

What has your extensive travelling and experience taught you about spirituality? Has it just confused you or has it made you certain of anything?

I’m not confused. I think the Buddhists have it mostly right. I think compassion and respect for living beings, whether people or animals, and not trying to wage war every five minutes. I think there’s all different ways to interpret experience and spirituality. I’m looking around at some of these major religions. I’m thinking, there’s something wrong here. I don’t get it. That’s my take on that. It’s as valid being a Hindu, a Sikh, a Zoroastrian. It’s all completely valid. The problem is when you disrespect me and you want to get in my face because I’m not adhering to your values and principles. It’s not about spirituality. There’s 1000s of ways to practice spirituality. The question is, what’s going on here? You wanna kill me based on the fact that I’m not in your camp? That’s the disconnect I have with these establishments.

There was a photo that went viral recently that reminded me of you. A Turkish photojournalist went to take a picture of a Syrian refugee girl and she put her hands in the air thinking it was a gun. That one image will do more to express the fear of refugees than probably any story. Why does a photo do that?

Well, it’s a frozen moment. A video, they move, you can’t go back to it. This thing you can go back to again and again. You can look at it for a minute, just stare at it and imagine and wonder. Pictures are much more powerful than video. Maybe with the exception of the video of that police officer murdering the black man who had his tail light out. I mean, wow, that’s like one of the most incredible things you’ll see.

One of your photos is of a kid pointing a gun at his head in Peru. The kid is weeping. It almost seems staged. How did you get that photo?

I’ll tell you the story. I was walking down the street, these kids were playing. They were tormenting him. This happened to me as a kid too. Some bullies are in his face. He held this toy gun to his head. It came about because these people in the neighbourhood were ridiculing him, beating him up. So he did that. I just happened to be walking by. I suspect that in the next five minutes things settled down. I think this is a normal event. But if you look at the picture it’s powerful. He’s weeping and has a distraught expression and what appears to be a real gun.

With that photo it’s the eyes that really tell you the story, you see the fear/pain. You’ve said the eyes are the most telling, evocative part of body. Why is that?

We look at each other with our eyes. On the face, there’s the mouth and eyes that tell the story. If somebody’s angry or sad, you’ll see it those two parts. We look at each other with our eyes, it’s a very major, telling feature. The emotion is told through the eyes. I don’t know another way to describe it.

We’re approaching the 30 year anniversary since you took the picture of Sharbat Gula (aka the Afghan Girl). She was in the news recently with reports claiming the national ID cards had been issued illegally from Pakistan. Do you know anything about that?

If you think about it, she’s an Afghan. She’s a refugee. She’s an orphan. There’s a mood in Pakistan that they are no longer welcoming to refugees. The picture starts to become clear. I think you or I, we would do what is right for ourselves and our family, she decided to do what’s right for her and her family. She’s been living in Pakistan since 1980. But she’s an adult. She’s free to do whatever she wants. The whole ID thing I’m not familiar with. I know the story, but we never spoke to her. She never spoke to us about these technical things. So, yeah, that’s pretty much it. I’m not sure how the situation has been involved.

You, and National Geographic, have been helping her so much. You bought her a house. National Geographic financially supports her. Is she able to live comfortable now?

You’d have to ask her that question. Let me just say for the record, National Geographic, together with her husband worked out an arrangement for compensation and assistance based on the fact that she had appeared in the magazine. They felt very connected and responsible. They wanted to do the right thing. That’s the point. She gets enormous amounts of support.

I read mixed reports online about where she lives. Is she still in a refugee camp?

No. If you believe everything you read, there’s a wonderful bridge in New York I want to sell you. It’s cheap. I’ll sell the whole thing for $75,000.

Well, I definitely don’t believe everything. So that’s why I’m glad I could clear that up with you. Lastly, on the Afghan Girl, why do you think some photos become iconic? Is it mostly luck?

I don’t know if it’s luck. There’s certain songs and artwork that resonate with people. Or poems. That’s a question I don’t know the answer to. Why would one movie be a big hit and another not be? Why would one song become iconic and another song which can be wonderful not be? You could write a whole essay or book on that.

I wanted to ask you about internalizing the hardships you photograph and have experienced. One famous photographer, Kevin Carter, famously killed himself because he had seen too much and…

But didn’t he have some depression? It wasn’t just the picture. That’s more to do with suicide than the picture.

That’s a fair point. Maybe it had more to do with how he was hardwired than what he say. But how do you internalize what you’ve seen? Do you have to remain detached?

I don’t really think about it. I see my war photography as a good thing. You have to realize that you’re trying to inform people and show them what’s happening, in the hope that things can change for the better. We have to know what’s happening in our world, to make choices about where we go moving forward.

Do you like being photographed?

I’m fine with that. I don’t have a problem with it.

Many dream of reaching the pinnacle of our professional fields. You’ve done that. Has it brought you happiness and contentment?

Well, I don’t see it that way. I get up in the morning. I come to the studio. I work. I enjoy photographing and telling stories. How I was living and photographing 20 years ago, I’m continuing that. I think if people respond to your work and appreciate your work, and they are moved, that’s great. If people appreciate my work that’s great. I’m grateful.

FOR MORE ON STEVE McCURRY:

1) Visit his website: www.stevemccurry.com

2) Follow him on Twitter, @McCurryStudios, and on Instagram @stevemccurryofficial

0 Comments