“Everybody reads, but I read like a maniac. I go deep down inside the text and bind it into my

heart so that it has an influence on my own writing. When I write a piece, I am making myself so close to the language that it is super intense and super exhausting.”

In an ocean of noise, I first heard your voice – Arcade Fire.

The internet is full of would be poets and cultural critics. Most of them fail to make an impact. Teju Cole, a Nigerian-American writer, photographer and art historian, is an exception.

Through his popular and creative Twitter account, his well-crafted essays and works of fiction, Cole has established himself as an influential literary voice.

Cole first appeared on my radar during the height of the KONY 2012 campaign. His essay for The Atlantic, “The White-Savior Industrial Complex,” which discussed the problematic nature of KONY 2012 and other “white savior” projects in Africa, went viral and ignited fierce debates. I enjoyed the piece because it provided a coherent argument on why the campaign was a misguided idea.

The article was inspired by seven tweets from Cole. Below are two of my favorite:

From that point, I quickly became a follower (on Twitter) of Cole. Turns out, the white savior tweets were only the beginning of his sharp social commentary. His Small Fates series, for example, crafted humorous, dark and clever tweets from bizaree stories in old Nigerian and American newspapers. Here’s a great example:“Together, the Devil and Eze broke into a pentacostal church in Iba on Sunday night and stole the offering, but only Eze was caught.” Or another, “Pastor Ogbeke, preaching fervently during a storm in Obrura, received fire from heaven, in the form of lightning, and died.”

Cole has pushed Twitter to new heights and attracted more than 100,000 people to follow along. Not only are followers treated to elaborate series, but also frequent thoughts and opinions, like this one: “Every 60 seconds in Africa, a minute passes. We can put a stop to this. Please retweet.”

Outside of Twitter, Cole expresses himself more fully in top publications like The New Yorker and The New York Times. He’s also published two novels: Everyday is for the Thief and Open City.

Open City, which was released in 2011, tells the story of a half-Nigerian half-German psychiatric student roaming the streets of New York City. The book reads like a stream of consciousness as the book’s narrator, Julius, encounters people and places in a post-9/11 New York. The prose is vivid and intricate, the descriptions vast. Cole is unapologetic about challenging his readers. The book won, and was nominated for, numerous literary awards.

The diverse nature of Cole’s work is a byproduct of his upbringing and taste. He was born in Kalamazoo, Michigan, but grew up in Lagos, Nigeria. These days he’s more of a New Yorker than anything, but he still considers Lagos home. Aside from all his writing accomplishments, he’s also in the midst of a Ph.D at Columbia University on 16th Century Dutch renaissance painter, Pieter Buregel. Cole is also a photographer. His work has been displayed in exhibitions around the world. He keeps a steady stream of pictures on his Flickr Photostream.

All in all, Cole is man dedicated to the arts and particularly with words, and figuring out ways to string them together to say something of worth.

I’ve been trying to track down Teju Cole for more than a year. In May of 2012, I emailed Teju’s publicist. A week later, I received an email, with several forwarded messages attached, kindly informing me that Teju was far too busy for an interview. This only confirmed my suspicion that he was highly in demand and made me want an interview even more.

And so, in Nairobi, I finally got my chance. Cole was in town for the StoryMoja Hay Festival. I caught up with him in the lobby of the Westhouse Hotel.

There is much I WANNA KNOW from a brilliant literary mind who wears nice, red-soled, shoes.

From writing, to Kanye West, to the power of Twitter, to getting robbed at gunpoint, we cover it all.

* * *

Kenya just christened its first female Maasai warrior, a white American. Is this the perfect example of the “White Saviour Industrial Complex?”

When I saw this article I thought, if you want to teach my essay and the issues it deals with, and you don’t cite the female warrior you’re wasting everyone’s time. It’s a note perfect example. That was also the reason I didn’t engage with it too much. It’s almost too obvious. Someone might suspect me of coming up with the whole thing.

Some might argue and say, “What’s wrong with her doing that?” What would you say to those people?

She can do exactly what she wants. It’s a free world. But not everyone can, or has, the opportunity to present themselves in a story in which they are the main protagonist. On the very basic level, it is Africa as a backdrop. Then there’s many layers to unpack within it: economic things, the saving that is more about the person that is doing the saving, the ego, the policy consequences of actually viewing other people as inferior. This is the material of a thousand Hollywood movies, whether it’s overseas with the Maasai or in the US with black characters. It’s assumed that the person whose story matters, and concerns are front and center, are white protagonists. That has real world consequences because the person whose story gets told is the reality that gets prioritized. For me as a novelist, and someone who does creative work in other forms such as Twitter, who is telling the stories and what story is being told matters very much.

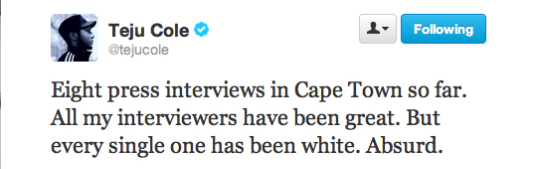

I was a little nervous about today because of your tweet from Cape Town.

(laughs) On a personal level, don’t worry. They were all terrifically well prepared. You’re not going to become the subject of a tweet or anything.

Actually, that would be a badge of honor.

Part of what happens with those things is that they are language acts, they are interventions. Sometimes I don’t need to write a whole essay about it, I just need to raise something from my own experience which other people are being too polite to mention. I heard back from a lot of white South Africans who had corrective things to say to me, but the word got out. I know for a fact that overwhelmingly black South Africans who read it were grateful that I had not come to their country as an innocent guest who was trying to white wash things from a place of privilege.

You’re credited as having a distinctive literary voice. How did you start to discover that?

I think it took quite a bit of time. With Open City, it was realizing that it had to have a certain rhythm and meditativeness. I had to trust that. Probably the biggest temptation that young writers face is to be entertaining, to show your bag of tricks and do a bit of tap dancing. I read a lot of things and I keep seeing this brocade of voice where someone is trying to be too pally with you or ingratiating on the page. In some cases it’s appropriate, but in others it’s like showing up for a funeral in ripped jeans. It’s like, OK, I know you’re rock & roll but there’s a reason people wear dark slacks to a funeral. I’m not saying the writing has to be somber, I’m just saying you have to trust the tonal space you’re in and not break out of it. It’s like method acting in a way.

Why do you think metaphors are such a powerful literary tool?

There’s a strange film I watched a few days ago that said, “Just because a camel is in Saudi Arabia does not mean it has been to Mecca.” I think there’s something about a fresh and original image. The question is why it should be so. There’s a connection between analogical thought and intelligence. It’s the ability to see among two unlike things what makes them similar. I’m always excited when someone says, he looks like Forrest Whitaker and most people would be like, no he doesn’t. That gap excites me. The fact that someone can see it because they’re picking something that is not so obvious.

I also think an overdependence of metaphor can be a sign of stupidity.

Every writer seems to have a period, before they hit their stride, where they sucked. Did you go through any periods where your work sucked and you now cringe looking back?

(laughs) I was lucky in the sense that I didn’t have a super intense writerly ambition. That doesn’t mean I didn’t work hard or care for it. You meet people who say they submitted their book 200 times and finally got it written. For every one person like that there’s hundreds of people who have made dozens of submissions with no traction. I didn’t want my life to be characterized by that kind of failure. I’m just going to do what I want to do and there’s no guarantees. What this allowed me to do was focus on the writing, far way from trying to please any editors. So today, the writing that I like the best is the writing that I have chosen to do myself and has little editorial intervention. I love being edited but if I write trying to please an editor it comes out sounding like everyone else. I’ve done a few pieces like that.

Twitter is one of your greatest platforms. Has Twitter now become an acceptable forum for writers?

There’s something about it that’s frivolous, and that’s what makes it interesting to me. Then it’s insurgent and people are reading Twitter as a hangout, it’s water cooler conversation. But I also know that people are hanging out here and I know that language has a gravity that can be affected if you deploy it affectively. As a political person, there are things I do wish to say about my place in the world, about people who don’t have a voice. I’m kind of aware that there are ways to get that across, sometimes through humour, sometimes through shocking or direct and violent language. I feel that more and more, the more followers I have. There are many people who know nothing of a world in which we take the reality of the “other” seriously. If I’m running on any platform, it’s that other people in other countries are really really real and there has to be a way or presenting their reality that is not condescending to them or about our psycho-social needs.

Do you think the popularity of Twitter has more to do with the power of brief, small sentences or more to do with waning attention spans?

Brevity is a part of it but language is the greater part, which is that human beings have always liked things that are well said. Poetry is one of the oldest things that we do. Lyrical poetry is not a big part of most people’s lives. Twitter now becomes an interesting way of getting cared for language into people’s space. Because there is something deep inside of us that responds to cared for language, whether it’s literary, poetry, or really good lyrics in a song. The idea that this sentence has been compiled out of the most ordinary tools has a mystery to it. I’m not trying to be a poet on Twitter, I’m trying to be aware of the fact that a very simple sentence well written can have a very moving affect without that person knowing why. There’s a deep genetic part of you that somehow, even without your permission, recognizes good language when it arrives.

I was pleasantly surprised to find out that you’re a fan of Rob Delaney. And equally surprised that you praised his use of the English language. What about Rob Delaney’s tweets do you appreciate?

Here’s the weirdest thing, before we got to know each other he and his wife read my book. They read it out loud to each other and loved it. There’s a game recognize game aspect to it, which says, “the way you put out a sentence matters.” He will often use sentence fragments, misspelled words, ironic forms of punctuation. He’s able to do it so effectively because he knows how a sentence works. I actually think he’s a fabulous writer. Apart from the funniness, he knows how to make a thought arrive. People think of 140 characters as small, I think of it as a lot. If an average words is 6 characters, over the course of 140 you have a lot of opportunities to screw it up.

Do you have a favorite Rob Delaney tweet?

My favorite tweet is not a dirty one, though they’re mostly dirty and I love them. It’s one of him being in a book shop in a kids’ section and he’s holding a book with the title, “Have you ever tickled a tiger?” And he wrote a little comment, “Um hello, I don’t have a DEATHWISH!!! #LOL.” Everytime I see that tweet, I just think it’s the funniest thing. Something works about it.

The other one I really love is, “Probably the scariest thing to come out of the Muslim world is Algebra.” He makes social interventions. He slaps people who are sleeping.

I’ve heard you say that you’re more proud of your photography than your writing. Do you stand by that?

At the end of day, there is something about words that is trying too hard. Pictures are just there. It didn’t exist in the world until I took the picture. There really isn’t anything quite like it. It’s like a visual poem. It’s a strange thing. It doesn’t feed anybody, it doesn’t massage anybody’s back, it doesn’t open any jail cells, it won’t stop a drone from striking, and yet here it is, it exists in the world and came in to the world through me. My top 20 pictures versus my top 20 pieces not published in a book, I’ll take my top 20 pictures.

You’ve become an extremely sought after individual in the past year or so. How are you handling the additional expectations?

There are people that are smarter than me, better looking, have better technical chops. Those things are out of my control. The one thing that’s in my control is how intense I am. I don’t have any excuse for letting anyone be as intense as I am. Everybody reads, but I read like a maniac. I go deep down inside the text and bind it into my heart so that it has an influence on my own writing. When I write a piece, I am making myself so close to the language that it is super intense and super exhausting. I think part of my sense of continuing to merit my place at this table, where I have a lot of readers and positive attention, is to make sure that there is nothing that is coasting. When I write a tweet, I take it through drafts. It’s not that I don’t believe in frivolity, but even my frivolity I want it to be intentional. That’s how I deal with success, by being ready.

We share a similar experience: We were both robbed at gunpoint. How did that experience change you?

Kind of a blank in that moment, a hesitation that could have cost my life. Afterwards it was a feeling of vulnerability, which is a terrible feeling. I have this very strong wish to live long and feeling that that was under threat for such pettiness. The guy who robbed me was high and could have shot me for things I had. It’s also more complicated layers of the class warfare. There are poor people without access to resources. There was also a real element of how I would narrate this experience to my readers, when I know they might cherry pick aspects of it and come to conclusions about Nigeria. The strongest part of the experience was feeling this is really unnecessary and feeling that life is very contingent, like “God is not protecting us.”

When I was robbed, I felt like I had experienced inequality in one of its most terrifying forms. Can you relate to that sentiment?

Poverty is a real problem, but people weren’t holding each other up at gunpoint in villages in Western Nigeria in 1950. You know what I mean? But there’s staggering wealth in Nigeria and poverty. The inequality is a driver of these things. When I think of world politics, I keep coming back to the idea that there are 7 billion of us on this planet and we all want stuff. Most people on earth wish to have a car and everybody wants online access. That’s a tall order to give to 7 billion. One of the solutions for people in the Western world is to completely ignore that and say people who want to be billionaires can be. You can be as rich as you want to be. That fundamental attitude, of extreme wealth, as a societal goal, and that dream to be a thousand times richer than your neighbor, that’s a strange dream to build your society around. But that’s what we’ve done in the U.S. That drives crime and unhappiness.

I know you’re a big rap fan. Do you ever freestyle in your spare time?

(laughs) I’ve decided to leave that to the masters. I actually think rap is harder than lyrical poetry. Black Star is that kind of album that has really good writing. Mos Def is a very good writer. But I think what they’re doing is harder than what poets are doing because delivery is such a big part of it. To write in a way that you know can be delivered well. I dabble in a lot of things, but I know that if I start now maybe 10 years I might be able to do something interesting.

So, if Mos Def contacted you and asked for a verse, would you give it a shot?

I’d find a way to rise to the occasion.

What are your thoughts on Yeezus?

I think that if you’re a young writer and you hear Black Skinhead and it doesn’t challenge you to be a more intense and a better creative person than you’re not serious. He’s not fucking around. He’s pretty amazing actually and he’s doing seriously creative work. He’s a big star and makes a lot of money but his work is as seriously creative as that of the most arcane classical music professor writing obscure scores in Princeton’s’ music department. Kanye is serious.

Pound of pound, what’s the best Radiohead album?

You’re not going to like it.

Don’t say “Pablo Honey.”

King of Limbs. Nobody expects that. Each album, and no music critic would ever agree with me, has been better than the one before. It’s a weird argument to make. The only exception being Kid A and Amnesiac, which are pretty much equal. OK Computer was good but there were two or three songs that were filler. But by the time you get to Hail to the Thief there’s only one weak song, Sail Away Softly. And then, King of Limbs, there were no weak songs.

Who would you choose to direct your biopic: Quentin Tarantino or Spike Lee?

Neither. Michael Haneke.

FOR MORE INFORMATION ON TEJU COLE:

1) Follow him on Twitter: @tejucole

2) Check out his website: www.tejucole.com

This was a really amazing interview. Glad you two managed to meet up!